From

icons and onion domes to suprematism and the Stalin baroque, Russian

art and architecture seems to many visitors to Russia to be a rather

baffling array of exotic forms and alien sensibilities. In fact, Russian

art and architecture are not nearly so difficult to understand as

many people think, and knowing even a little bit about why they look

the way they do and what they mean brings to life the culture and

personality of the entire country. From

icons and onion domes to suprematism and the Stalin baroque, Russian

art and architecture seems to many visitors to Russia to be a rather

baffling array of exotic forms and alien sensibilities. In fact, Russian

art and architecture are not nearly so difficult to understand as

many people think, and knowing even a little bit about why they look

the way they do and what they mean brings to life the culture and

personality of the entire country.

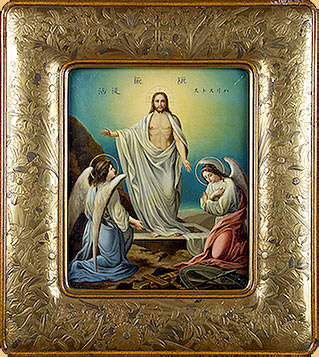

In old Russia nearly every phase of life was colored by religion.

Every day in the calendar was dedicated to the observation of some

saint. Every individual and every trade had their patron saints. A

distinctly Russian form of representing saints and religious themes

is the icon.

|

|

|

A bit of

a History

Russia's unique and vibrant culture developed, as did the

country itself, from a complicated interplay of native Slavic

cultural material and borrowings from a wide variety of foreign

cultures. In the Kievan period (c. 10th–13th centuries)

the borrowings were primarily from Eastern Orthodox Byzantine

culture. During the Muscovite period (c. 14th–17th centuries)

the Slavic and Byzantine cultural substrates were enriched and

modified by Asiatic influences carried by the Mongol hordes.

Finally, in the modern period (since the 18th century) the cultural

heritage of western Europe was added to the Russian melting

pot.

Although many traces of the Slavic culture that existed

in the territories of Kievan Rus survived beyond its Christianization

(which occurred, according to The Russian Primary Chronicle,

in AD 988), the cultural system that organized the lives of

the early Slavs is far from being understood. From the 10th

century on, however, enough material has survived to give

a reasonable portrait of Old Russian cultural life. High culture

in Kievan Rus was primarily ecclesiastical. The level of literacy

was low, and artistic composition was undertaken almost exclusively

by monks. The earliest literary works to have circulated were

translations from Greek into Old Church Slavonic.

|

|

Unlike the pictorial tradition

that westerners have become accustomed to, the Russian icon

tradition is not about the representation of physical space

or appearance.

Icons

are images intended to aid contemplative prayer, and in that

sense they're more concerned with conveying meditative harmony

than with laying out a realistic scene. Icons

are images intended to aid contemplative prayer, and in that

sense they're more concerned with conveying meditative harmony

than with laying out a realistic scene.

Rather than sizing up the figure in an icon by judging

its distortion level, take a look at the way the lines that

compose the figure are arranged and balanced, the way they move

your eye around. If you get the sense that the figures are a

little haunting, that's good.

|

They weren't painted to be

charming but to inspire reflection and self-examination. If

you feel as if you have to stand and appreciate every icon you

see, you aren't going to enjoy any of them. Try instead to take

a little more time with just one or two, not examining their

every detail but simply enjoying a few moments of thought as

your eye takes its own course.

|

A silver-mounted triptych icon painted

with the Virgin Mary within a seed pearl border flanked by St.

Sophia (left) and St. Mathew (right).

A silver-mounted triptych icon painted

with the Virgin Mary within a seed pearl border flanked by St.

Sophia (left) and St. Mathew (right). |

|

Andrey

Rublyov Museum

During

the 14th century in particular, icon painting in Russia took

on a much greater degree of subjectivity and personal expression.

The most notable figure in this change was Andrey Rublyov, whose

works can be viewed in both the Andret Rublyouv Museum and the

Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, as well as the Russian Museum in

St. Petersburg. During

the 14th century in particular, icon painting in Russia took

on a much greater degree of subjectivity and personal expression.

The most notable figure in this change was Andrey Rublyov, whose

works can be viewed in both the Andret Rublyouv Museum and the

Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, as well as the Russian Museum in

St. Petersburg.

Named after the 14th century Russian monk and legendary

icon painter, the Andrey Rublyov Museum boasts the best collection

of works by the artist and houses permanent exhibitions of

icons of the Moscow School from the 15th and 16th centuries,

sculptures from the 12th to the 17th centuries and various

religious frescoes.

|

Little is known of Rublyov's life but it is thought that

he was born about 1360 and worked as an assistant to another

great icon painter, Theophanes the Greek, who came to Russia

from Constantinople. Fairly late in life, Rublyov became

a monk, first at the Trinity St. Sergius Monastery in Sergiyev

Posad and then at the Andronikov Monastery in Moscow.

Little is known of Rublyov's life but it is thought that

he was born about 1360 and worked as an assistant to another

great icon painter, Theophanes the Greek, who came to Russia

from Constantinople. Fairly late in life, Rublyov became

a monk, first at the Trinity St. Sergius Monastery in Sergiyev

Posad and then at the Andronikov Monastery in Moscow.

|

Russian

painters did not sign their works until the 17th century, so

paintings can only be assigned to Rublyov on the basis of written

evidence or of style. Extensive written evidence has linked

the medieval painter with wall paintings in Vladimir as well

as those at the Andronikov and other monasteries in Moscow. Russian

painters did not sign their works until the 17th century, so

paintings can only be assigned to Rublyov on the basis of written

evidence or of style. Extensive written evidence has linked

the medieval painter with wall paintings in Vladimir as well

as those at the Andronikov and other monasteries in Moscow.

|

A

large number of icons have also been attributed to him, many

of which are housed in the museum or on display at the Tretyakov

Gallery. Rublyov was trained wholly in the Byzantine tradition,

in which the spiritual essence of art was regarded as more important

than naturalistic representation. A

large number of icons have also been attributed to him, many

of which are housed in the museum or on display at the Tretyakov

Gallery. Rublyov was trained wholly in the Byzantine tradition,

in which the spiritual essence of art was regarded as more important

than naturalistic representation. |

|

By the 14th century, this style had given way to a more

intimate, humanistic approach, and to this Rublyov was able

to add an element that was truly Russian, a complete unworldliness,

and it is this that distinguishes his work from that of his

Byzantine predecessors.

|

The

museum holds regular temporary exhibitions of icons and religious

works and is housed in the former Andronikov Monastery, which

was originally founded in 1360 by the then Metropolitan of Moscow,

Alexei. Excursions round the museum include a look inside the

monastery's working Spassky Cathedral, thought to be the oldest

building in Moscow and still bearing traces of murals believed

to have been painted by Rublyov himself. The

museum holds regular temporary exhibitions of icons and religious

works and is housed in the former Andronikov Monastery, which

was originally founded in 1360 by the then Metropolitan of Moscow,

Alexei. Excursions round the museum include a look inside the

monastery's working Spassky Cathedral, thought to be the oldest

building in Moscow and still bearing traces of murals believed

to have been painted by Rublyov himself.

Click

here to see more of Rublyov's icons.

|

|

|

Links

The best collections of icons are to be found in the Tretyakov

Gallery (official website,

russian only) and the Russian Museum (official

website), though of course many Russian churches have preserved

or restored their traditional works.

Article about "Religion

in the Former Soviet Republics".

If you wish to purchaise Russian Icons or some other quality

Russian gifts and collectibles please visit the Russian

Store website. |

|

Painted

on wood, icons are known to the Russians as "obraz", but

we know them better by the term icon, which comes from the Greek word

for picture or likeness, "eikonoi". The painting of icons

is the most distinctive art form of old Russia, and Russian icons

are the most varied and beautiful of all. Painted

on wood, icons are known to the Russians as "obraz", but

we know them better by the term icon, which comes from the Greek word

for picture or likeness, "eikonoi". The painting of icons

is the most distinctive art form of old Russia, and Russian icons

are the most varied and beautiful of all.

Until recently, there was not much interest in icons. Even

in Russia, where they were common, icons were taken for granted. But

today old Russian icons are recognized as works of art by art historians

and collectors alike.

|

|

|

Collectors of icons should remember that the best and most

valuable icons are to be found in Soviet and European museums. A

great many, of course, have found their way to America and private

collectors. From time to time, early and rare icons are offered

for sale by prestigious auction galleries and normally bring very

high prices. Also, icons a century or two old are still found occasionally

in some better known antique shops.  But

the majority of icons offered today are often of inferior quality.

The collector must be careful because a number of known fakes turn

up in the market now and then. When purchasing an icon it is best

to enlist help from a reputable expert. But

the majority of icons offered today are often of inferior quality.

The collector must be careful because a number of known fakes turn

up in the market now and then. When purchasing an icon it is best

to enlist help from a reputable expert.

Icon painting in Russia, as elsewhere, has followed traditional

canons. As a consequence, icons can be so like one another that

at times it is scarcely possible to distinguish between them. This

is why icons representing the same subject, although they were painted

centuries apart, can be so similar.

|

One

must keep in mind that the forms of the Russian icon remain unchanged

through the centuries. One

must keep in mind that the forms of the Russian icon remain unchanged

through the centuries.

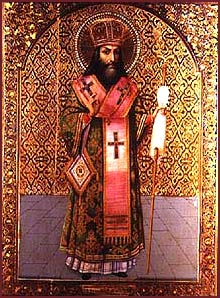

Icons are naturally divided according to subject into two main

groups; painted icons which simply depict holy personages and icons

which depict scenes from the Scriptures or events from the lives of

the saints. Icons from the latter category serve a didactic purpose.

They have served, so to say, as an attractive and effective teaching

tool. On the other hand, icons which represent individual saints have

been the object of veneration.

|

|

The Birth of Christ, 18 th Century

icon, Orthodox Style.

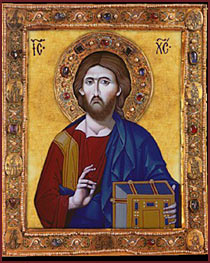

In Russian iconography, literally hundreds of themes have been represented.

Images of Christ are numerous, with the type known as 'The Saviour

Not Made by Hands' being perhaps the most popular of the Christ

representations in old Russia. There are also other representations

of Christ including depictions of the events of his life.

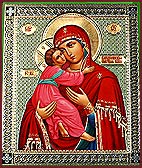

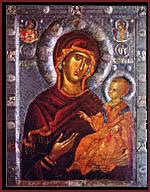

The enormous and varied iconography of the Virgin is even more

impressive. There are no less than three hundred types, all different.

In the Milwaukee Public Museum collection, some better known icons

of the Virgin are: 'The Virgin of Vladimir', sometimes referred to

as 'the most ancient hymn to motherhood', 'The Virgin of Tykvin',

'The Virgin of Kazan' and 'The Virgin of Shuja'. This profusion of

types if also evident in the depiction of the most popular saint of

old Russia, St. Nicholas of Myra.

|

|

The

Festivals of the Church was another theme popular with icon painters.

Icons of this type were used in sets consisting of twelve or sixteen

scenes from the Scriptures. Furthermore, old native Russian saints

and numerous icons have preserved their images, including events

from their lives. The

Festivals of the Church was another theme popular with icon painters.

Icons of this type were used in sets consisting of twelve or sixteen

scenes from the Scriptures. Furthermore, old native Russian saints

and numerous icons have preserved their images, including events

from their lives.

The old Russian icons are not uniform in quality, all the

more so because they were created at various times and in different

icon painting centers.

The Virgin of Shuja is an excellent example of a tempera on

wood. This icon was painted on a wood panel. In order to prevent warping,

diagonal strips of wood were applied on the back. The edges of the

panel rise above the picture space from the frame. The colors were

mixed with egg yolk and diluted with kvas, a popular Russian drink

made from sour bread. The completed painting was given a coat of a

special varnish. This varnish at first enhanced the colors, but turned

dark and opaque later, producing the contrary effect. The metal frame

and halo, in the form of a crown, were added much later.

|

|

The Old Testament Trinity. 19 th Century

AD to 20 th Century AD,

Tempera on Wood, Russian Orthodox Style.

In addition to icons painted on wood, there are a number

of icons and religious objects made of metal. Most of these icons

date from the 19th century. The design is engraved on the metal

or the background cut away to leave the figures in relief and then

perhaps filled in with white or blue enamel. There is a great variety

of these icons including typical Russian crosses made in the same

manner.

|

|

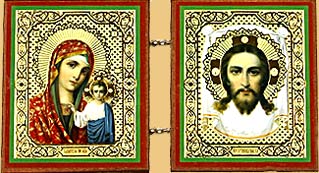

A

17th century metal icon mold might continue to be used well

into the 20th century. A very attractive brass quaditych, for example,

was cast from an old mold in Belgium in the 1950's. This is not

unusual. Many modern copies have been made in the old style and

sold to unsuspecting people in Russia and Europe. These small brass

icons sometimes consist of a single panel, of two or three panels

hinged in the form of triptych or occasionally even a larger number

of panels. They were carried by individuals for private worship. A

17th century metal icon mold might continue to be used well

into the 20th century. A very attractive brass quaditych, for example,

was cast from an old mold in Belgium in the 1950's. This is not

unusual. Many modern copies have been made in the old style and

sold to unsuspecting people in Russia and Europe. These small brass

icons sometimes consist of a single panel, of two or three panels

hinged in the form of triptych or occasionally even a larger number

of panels. They were carried by individuals for private worship.

In a further departure from classic icons, the 19th century

brought many changes. It was a period of decline, commercialism

and mechanical reproduction. A number of icon handcraft shops were

established in which cheap metal icons were produced. Icons were

printed in color on time and became very popular.

|

|

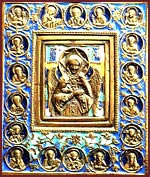

In

another development, enterprising craftsmen took advantage of technical

innovations and made metal coverings in factories. These metal coverings,

or "riza", were originally applied to icons toward the

end of the 17th century. Intended only as a partial covering of

silver, gold, or cheaper metal, the riza covers the entire painting

except faces, hands and feet. Later craftsmen, however, no longer

bother to paint the entire panel of the icon but only those parts

of the figures which were to remain visible. In

another development, enterprising craftsmen took advantage of technical

innovations and made metal coverings in factories. These metal coverings,

or "riza", were originally applied to icons toward the

end of the 17th century. Intended only as a partial covering of

silver, gold, or cheaper metal, the riza covers the entire painting

except faces, hands and feet. Later craftsmen, however, no longer

bother to paint the entire panel of the icon but only those parts

of the figures which were to remain visible.

However, it would be wrong to conclude that icons of great

charm and value were not produced in the recent past. A number of

craftsmen still continued to produce more expensive icons and preserved

the integrity of icon painting.

|

For 70 years, during Soviet

era, when religion was forbidden in Russia, icons lost its popularity.

Then came Gorbachev's

more general tolerance towards religion and the election of Patriarch

Alexy and the Metropolitan Cyril of Smolensk. The revival of religion

in Russia and the former Soviet republics brought icons back to the

Russian home. Many Russians lately have become avid collectors of

old icons. As a matter of fact, icons are in great demand the world

over, not necessarily as religious objects but for their intrinsic

artistic and historical value.

|

| |

icons | matreshka |

samovar | zhostovo

trays | lacquerwork | traditional

dress | soviet

era

|

|

From

icons and onion domes to suprematism and the Stalin baroque, Russian

art and architecture seems to many visitors to Russia to be a rather

baffling array of exotic forms and alien sensibilities. In fact, Russian

art and architecture are not nearly so difficult to understand as

many people think, and knowing even a little bit about why they look

the way they do and what they mean brings to life the culture and

personality of the entire country.

From

icons and onion domes to suprematism and the Stalin baroque, Russian

art and architecture seems to many visitors to Russia to be a rather

baffling array of exotic forms and alien sensibilities. In fact, Russian

art and architecture are not nearly so difficult to understand as

many people think, and knowing even a little bit about why they look

the way they do and what they mean brings to life the culture and

personality of the entire country. During

the 14th century in particular, icon painting in Russia took

on a much greater degree of subjectivity and personal expression.

The most notable figure in this change was Andrey Rublyov, whose

works can be viewed in both the Andret Rublyouv Museum and the

Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, as well as the Russian Museum in

St. Petersburg.

During

the 14th century in particular, icon painting in Russia took

on a much greater degree of subjectivity and personal expression.

The most notable figure in this change was Andrey Rublyov, whose

works can be viewed in both the Andret Rublyouv Museum and the

Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, as well as the Russian Museum in

St. Petersburg.

Little is known of Rublyov's life but it is thought that

he was born about 1360 and worked as an assistant to another

great icon painter, Theophanes the Greek, who came to Russia

from Constantinople. Fairly late in life, Rublyov became

a monk, first at the Trinity St. Sergius Monastery in Sergiyev

Posad and then at the Andronikov Monastery in Moscow.

Little is known of Rublyov's life but it is thought that

he was born about 1360 and worked as an assistant to another

great icon painter, Theophanes the Greek, who came to Russia

from Constantinople. Fairly late in life, Rublyov became

a monk, first at the Trinity St. Sergius Monastery in Sergiyev

Posad and then at the Andronikov Monastery in Moscow.  But

the majority of icons offered today are often of inferior quality.

The collector must be careful because a number of known fakes turn

up in the market now and then. When purchasing an icon it is best

to enlist help from a reputable expert.

But

the majority of icons offered today are often of inferior quality.

The collector must be careful because a number of known fakes turn

up in the market now and then. When purchasing an icon it is best

to enlist help from a reputable expert.