|

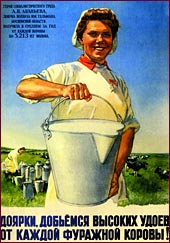

After

almost twenty years of hardship from the Five Year Plans,

the purges, and World War II, the Soviet

people were hoping for a freer, more prosperous life. But

those hopes were quickly dashed as the Cold War began. After

almost twenty years of hardship from the Five Year Plans,

the purges, and World War II, the Soviet

people were hoping for a freer, more prosperous life. But

those hopes were quickly dashed as the Cold War began.

Stalin launched a fourth Five-Year

Plan in 1946 to bring a quick recovery from the wartime destruction,

and announced that austerity, hard work, and rigid discipline

would continue for some time to come. He pointed out that

the ultimate enemy of the Soviet Union, capitalism, was still

around, and that "so as capitalism existed, the world

would not be free from the threat of war." Therefore

Soviet citizens would have to be ready for yet more sacrifices

and dangers.

|

|

Always

preoccupied with security, Stalin spent the postwar years further

strengthening his control over the country. He was so thorough

at this, in fact, that the years 1945-53 are the most repressive

in Soviet history. Western art, literature, clothing and lifestyles

(even jazz) were banned, and foreign tourists were not allowed

to visit the USSR until 1958. During and immediately after the

war 1,250,000 people from seven ethnic groups of dubious loyalty

(Volga Germans, Crimean Tatars, Kalmucks, and four smaller minorities

from the Caucasus) were accused of collaboration with the Nazis

and deported to Central Asia and Siberia. Always

preoccupied with security, Stalin spent the postwar years further

strengthening his control over the country. He was so thorough

at this, in fact, that the years 1945-53 are the most repressive

in Soviet history. Western art, literature, clothing and lifestyles

(even jazz) were banned, and foreign tourists were not allowed

to visit the USSR until 1958. During and immediately after the

war 1,250,000 people from seven ethnic groups of dubious loyalty

(Volga Germans, Crimean Tatars, Kalmucks, and four smaller minorities

from the Caucasus) were accused of collaboration with the Nazis

and deported to Central Asia and Siberia.

|

|

The

unruly Ukrainians were next on Stalin's blacklist, but even

he had to concede that there were not enough trains in the

USSR to get rid of all 40 million of them. Stalinist rule

was toughest in those areas that had just come under Soviet

rule since 1939, and the Catholics living in those areas were

regarded as untrustworthy and forced to join the Orthodox

Church. This resulted in a strange spectacle as the officially

atheistic Soviet state threw its powers of coercion behind

the Orthodox clergy. The

unruly Ukrainians were next on Stalin's blacklist, but even

he had to concede that there were not enough trains in the

USSR to get rid of all 40 million of them. Stalinist rule

was toughest in those areas that had just come under Soviet

rule since 1939, and the Catholics living in those areas were

regarded as untrustworthy and forced to join the Orthodox

Church. This resulted in a strange spectacle as the officially

atheistic Soviet state threw its powers of coercion behind

the Orthodox clergy.

At the same time came new episodes of anti-Semitism.

Officially it was justified on the grounds that many Jews

in the Red Army had defected to the West from East Germany,

and Stalin suspected that Soviet Jews were sending military

secrets to their relatives in the United States. But little

actual persecution took place until the establishment of the

state of Israel in 1948. This was because many Israelis were

socialists and/or immigrants from the USSR, giving Stalin

some hope that Israel would join the Soviet Bloc after independence;

the USSR even voted for the 1947 UN mandate that created the

Jewish state. But because Israel is a parliamentary democracy,

the Israelis have preferred to ally themselves with the West

almost from the beginning. The final blow came when the first

Israeli ambassador to the Soviet Union, Golda Meir, came to

Moscow and received an enthusiastic welcome from Soviet Jews

that made Stalin intensely jealous. Jewish organizations were

suppressed by the state, and Jews in the Communist Party were

removed from their posts. To avoid comparisons with the pogroms

of the tsars, Stalin called this campaign "anti-Zionism."

|

In

February 1953, nine doctors, most of them Jewish, were accused

of poisoning Andrei A. Zhdanov (the Leningrad party chief and

Stalin's favorite minister from 1934 to 1948), and of plotting

to do in other generals and Politburo members. During the previous

year Stalin called his henchmen spies, and Molotov lost his

position as foreign minister because of his Jewish wife; she

was sent to a labor camp without her husband even protesting.

Alleged "Titoists" and "Zionists" were already

being arrested andput on trial in eastern Europe. A new wave

of purges, especially an anti-Jewish one, appeared to be beginning,

and plans were made to deport all Soviet Jews to an autonomous

region set aside for them on the border of Manchuria. But fate

intervened; Stalin died of a cerebral hemorrhage on March 5,

1953. The politburo quickly released the victims of "the

Doctor's Plot." In

February 1953, nine doctors, most of them Jewish, were accused

of poisoning Andrei A. Zhdanov (the Leningrad party chief and

Stalin's favorite minister from 1934 to 1948), and of plotting

to do in other generals and Politburo members. During the previous

year Stalin called his henchmen spies, and Molotov lost his

position as foreign minister because of his Jewish wife; she

was sent to a labor camp without her husband even protesting.

Alleged "Titoists" and "Zionists" were already

being arrested andput on trial in eastern Europe. A new wave

of purges, especially an anti-Jewish one, appeared to be beginning,

and plans were made to deport all Soviet Jews to an autonomous

region set aside for them on the border of Manchuria. But fate

intervened; Stalin died of a cerebral hemorrhage on March 5,

1953. The politburo quickly released the victims of "the

Doctor's Plot."

|

|

|

|

In 1970s, Leonid Brezhnev, as general

secretary of the Communist party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),

had become the next prominent Soviet leader.

Decades of imperfect one-man rule convinced the Kremlin

that no Soviet leader should be allowed to wield as much power

as Stalin and Khrushchev did, so the Politburo gave the positions

of premier and secretary-general to two different members, Alexei

N. Kosygin and Leonid I. Brezhnev. The arrangement worked for

most of the 60s, with Kosygin running the government and Brezhnev

running the Party; during this time Kosygin was the more visible

of the two because of his trips abroad. But Russia's political

traditions, shaped by a psychological need for a single strong

father figure, gradually reasserted themselves. By 1970 the

technocratic Kosygin had been pushed out of the limelight by

the party man, Brezhnev.

There were many changes in domestic policies under Brezhnev

& Kosygin, but Soviet foreign policy remained pretty much

the same.

Brezhnev's tenure was marked by a determined emphasis

on domestic stability and an aggressive foreign policy. The

country entered a decade-long period of stagnation, its rigid

economy slowly deteriorating and its political climate becoming

increasingly pessimistic.

Seventies are generally known as the years of stagnant stability

in the USSR.

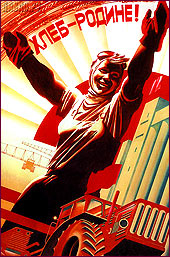

If the Soviet economy stagnated under Brezhnev, the armed

forces never had to go hungry. Every year the defense budget

increased; indeed, it has been estimated that the amount spent

on defense, space, and nuclear energy may have been as high

as 20-25% of the GNP. Since most of the manned and unmanned

space missions carried military payloads of one sort or another,

the space program also got everything it wanted.(17) By 1968

the Soviet nuclear arsenal had grown to match that of the United

States, but the buildup continued without interruption, until

the Soviet Union had the largest war machine in history.

When Breshnev died in 1982 he was succeeded as general

secretary first by Yuri

Andropov, head of the KGB, and then

by Konstantin Chernenko, neither of whom managed to survive

long enough to effect significant changes. In March of 1985,

when Mikhail Gorbachev became

general secretary, the need for reforms was pressing.

|

|