Yuri

Andropov Yuri

Andropov

Yuri Andropov (1914-1984) ruled the country for only 15 months.

Before that, for 15 years he had been heading the agency

which many came to fear and despise - the KGB.

And still, the recent poll shows that Andropov is recognized

as the most popular Soviet leader.

Andropov's career in the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs

was distinguished and certainly helped his rise to the highest

levels of the Party. He was regarded by most as intelligent,

wise, and skillful, obviously a substantial cut above his Party

peers, and with an impeccable Party record. In 1967, as he turned

53, he was made head of the Committee for State Security, known

throughout the world by its acronym - KGB. This promotion and

his great success in making the KGB the most famous and feared,

most notorious and effective internal control apparatus and

global intelligence operation on earth, made Andropov's rise

to the absolute pinnacle of Soviet power virtually inevitable.

Many in the West were surprised by Yuri Andropov's rapid

seizure of power in the Soviet Union following Leonid Brezhnev's

death in November 1982. Speculation had been widespread among

Western pundits and analysts during the preceding several months

that the successor would be another of the Politburo members

such as Konstantin Chernenko, Brezhnev's apparent favorite,

or Andrei Gromyko, the longtime Foreign Minister so well known

in the West. Andropov, head of the KGB until June 1982, was

given little chance, because other Politburo members would not,

could not support the idea of turning so much power over to

the recent head of the feared KGB.

But it was not primarily Andropov's position as KGB

chief that enabled him to gain the top position in the Politburo.

He had already moved into a position of strength in the Politburo

following the death of Mikhail Suslov in January 1982. Suslov,

senior Party ideologue and intellectual, had been the power

behind the throne of both Brezhnev and Khrushchev. Yuri Andropov

succeeded him. For Andropov, this was the climax of a pattern

throughout his rise - a pattern woven from the support of

important and influential friends at each stage of his career,

from his own intellectual strength, from years of careful

and clever maneuvering.

The scenario for the Politburo "election"

had apparently been worked out in advance, and when the successor

to Brezhnev was to be named, went something like this: Chemenko,

who was supposed to be the heir apparent, and as senior Party

Secretary present, stunned the group by nominating Yuri Andropov.

After some muttering but no real discussion, Chemenko then

asked the standard question, "Has

anyone anything to say against this candidate?"

Not only stunned, but also fearful from the evidence

that something was going on about which they knew nothing,

the other Politburo members kept quiet. No one wished to criticize

before the others the man who not only had been chief of the

secret police for fifteen years, but also now appeared likely

to become their new boss. Nothing was said. Chernenko then

observed, "It seems to be unanimous

that Yuri Alexanderovich Andropov is our new General Secretary."

And it was, though neither an accident, nor should it have

been as much of a surprise as it appears to have been.

After the inauguration, Andropov took a tough course

to rule the country. He had to fight both with negligent officials,

which were corrupted with power, as well as with Soviet people,

which were corrupted with laziness, irresponsibility, and

drunkenness. He wanted to retrieve law and order in the Soviet

empire with the help of tough police campaigns. He was a policeman

in his nature and skills. His actions were always in compliance

with his thoughts. Andropov arranged a grand cleansing process

amid top officials of the Soviet government. More than one-third

of senior officials were dismissed from their positions both

in the Central Committee of the Communist Party and in the

Council of Ministers. Andropov reached out to USSR-s regions

too: 47 of 150 regional high-ranking officials were fired.

Andropov may feel that stronger measures are required. All

these does not come as any great surprise to the long-suffering

Soviet people. In fact, knowing Andropov's record as KGB chief,

they tend to expect the worst.

Without question, Andropov was the toughest, most clever

and shrewd Soviet politician since Stalin, and possibly of

all Soviet leaders. He was not likely to be easily fooled,

and only a fool would fool with him. His could only be a one-man

dictatorship.

Much of Andropov's unease comes over concern for the

great power held by the Soviet military establishment. Khrushchev

had needed the strong support of war hero Marshal George Zhukov

to overcome Party and other resistance to his ambitions. Andropov's

fifteen years as KGB head could not but have made him acutely

aware of the chronic hostility the military has for the secret

police. Accordingly, shortly after the Politburo election,

Andropov made a speech to the senior military officers. It

must have sounded almost too good to be true to the assembled

marshals, generals, and admirals. In effect, Andropov told

them precisely what they wanted to hear: We will see that

you get the best weapons and other armaments. The troops,

especially the field grade and senior officers, will receive

even higher pay. The Soviet budget can and will sustain all

that is necessary to guarantee that the Soviet military establishment

will be superior to any in the world. Furthermore, there is

a long-range cruise missile now under test that will be superior

to anything the Americans have.

Such a speech, whether or not Andropov was bluffing

or lying, was bound to bring his audience to their feet, cheering

and slapping each other on the back, congratulating themselves

on their new leader. But Andropov apparently was not bluffing

about the new cruise missile. It should be realized that some

of the weapons research for the Soviet military is carried

out at KGB installations such as the closed city of Dubna,

a short distance north of Moscow. Dubna is an unusual place-a

heavily guarded city which few of the top-level research physicists

and other scientists working there are ever allowed to leave.

All work at the center is carefully overseen by KGB experts

working side by side with their civilian counterparts. It

does seem more than a little unusual, however, that senior

military commanders could be unaware of the development of

an important new weapon. But stranger things than that continue

to take place in the secretive Soviet system.

Former KGB agent-s information about his former boss

was revealed in European and American newspapers in the summer

of 1982. That information created a conception of Andropov

as of a pro-Western person. Andropov was known for his perfect

English. He was a fan of jazz, American mystery books and

whiskey; A patron of arts as he was presented by the KGB propaganda

machine; An intellectual and a poet as he remained in the

memories of his employees.

But he was also a suppressor of the 1956 Budapest uprising,

a persecutor of dissidents and an inventor of punitive psychiatry

as he has recently been described. It was also during Andropov's

time as Soviet leader that Soviet forces shot down a civilian,

South Korean airliner, killing all 269 people on board.

Although he was a hardliner, Andropov was responsible

for the rise to power of a group of younger, more liberal

officials, including Michael Gorbachev. Scholars

still debate whether Andropov would have proved to be a real

reformer had he lived.

|

|

|

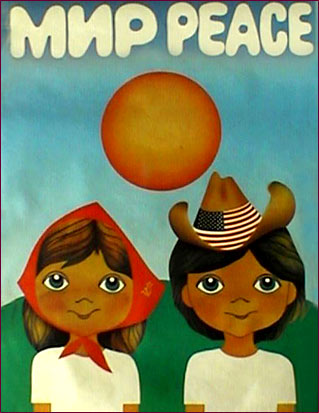

Soviet Poster - "Peace"

in Russian and English.

|

|

Samantha

Smith Samantha

Smith

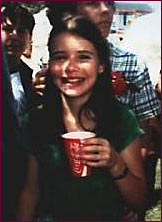

In 1983, at the height of the Cold War nuclear arms race, Samantha

Smith, a ten-year-old girl from the small town of Manchester,

Maine, wrote a letter to former Soviet president Yuri Andropov

pleading for a peaceful resolution to US-Soviet tensions. Samantha’s

story became an international headline and more importantly,

powerful propaganda that marked the beginning of the denouement

of the Cold War.

Dear Mr. Andropov,

My name is Samantha Smith. I am ten years old.

Congratulations on your new job. I have been worrying about

Russia and the United States getting into a nuclear war. Are

you going to vote to have a war or not? If you aren't please

tell me how you are going to help to not have a war. This question

you do not have to answer, but I would like to know why you

want to conquer the world or at least our country. God made

the world for us to live together in peace and not to fight.

Sincerely,

Samantha Smith

Little did Samantha realize the tremendous impact the

letter would have on her future. After she had written it, her

life went on as before. She continued with her studies at Manchester

Elementary School in Manchester, Maine, where she was a fifth

grader.

A few months later, Samantha received a letter from Mr. Andropov.

Samantha couldn't believe it. Until then, she wasn't sure that

President Andropov had even received her letter!

Mr. Andropov's letter to Samantha was more than two pages

long. In it, he compared Samantha to the fictional character

"Becky Thatcher"

in Mark Twain's famous novel Tom Sawyer. He called Samantha

"courageous and honest,"

telling her that the Soviet Union was "trying

to do everything so that there will not be war between our countries."

When asked by reporters what she thought of Andropov's response

she said it read like "a letter

from a friend." But that wasn't what really

excited Samantha. At the close of his letter, Andropov invited

Samantha to visit the Soviet Union to see for herself what the

people and the country were like.

Samantha and her parents decided to accept Mr. Andropov's

invitation. She toured the country; met with the first woman

in space, Valentina Tereshkova; met with the U.S. ambassador;

and attended the Soviet youth camp Artek, on the Black Sea.

People in both the Soviet Union and the United States watched

Samantha on TV. Samantha won their hearts. She was friendly

and cheerful, a beautiful child with a big smile. Staying in

a dormitory with nine other girls, Samantha spent her time swimming,

talking, and learning Russian songs and dances. She found that

many of her new friends were also concerned about peace. Later

Samantha wrote a book about her trip. On the first page she

wrote, "I dedicate this book to

the children of the world. They know that peace is always possible."

Gradually, Samantha Smith came to be recognized as a

world-wide representative for peace. Tragically, in August 1985,

however, Samantha and her father were killed in an airplane

crash. The little girl who believed that "people can get

along" was gone. She was thirteen years old. But Samantha

will not be forgotten. The Soviet government issued a stamp

in her honor, and also named a diamond, a flower, a mountain,

and a planet after her. Samantha's home state of Maine also

paid tribute to the diminutive ambassador. A life-size statue

of Samantha releasing a dove with a bear cub at her side (the

bear is a symbol for both Maine and Russia) was dedicated near

the Maine state capitol in Augusta. |

|

Links

article

"The Andropov Hoax", about

Samantha Smith. About

the Samantha Smith Foundation. (in English).

|

|

|