The

basic organizational structure of the KGB (Organization of the

Committee for State Security) was created in 1954, when the

reorganization of the police apparatus was carried out. In the

late 1980s, the KGB remained a highly centralized institution,

with controls implemented by the Politburo through the KGB headquarters

in Moscow. The

basic organizational structure of the KGB (Organization of the

Committee for State Security) was created in 1954, when the

reorganization of the police apparatus was carried out. In the

late 1980s, the KGB remained a highly centralized institution,

with controls implemented by the Politburo through the KGB headquarters

in Moscow.

During Soviet times, the secret police, under its various

designations, earned a notorious reputation as the eyes and

ears - and often executioner - for the state.

The KGB had a broad network of special departments in

all major government institutions, enterprises, and factories.

They generally consisted of one or more KGB representatives,

whose purpose was to ensure the observance of security regulations

and to monitor political sentiments among employees. The special

departments recruited informers to help them in their tasks.

A separate and very extensive network of special departments

existed within the armed forces and defense-related institutions.

|

Although

a union-republic agency, the KGB was highly centralized and

was controlled rigidly from the top. The KGB central staff kept

a close watch over the operations of its branches, leaving the

latter minimal autonomous authority over policy or cadre selection.

Moreover, local government organs had little involvement in

local KGB activities. Indeed, the high degree of centralization

in the KGB was reflected in the fact that regional KGB branches

were not subordinated to the local soviets, but only to the

KGB hierarchy. Thus, they differed from local branches of most

union-republic ministerial agencies, such as the MVD, which

were subject to dual subordination. Although

a union-republic agency, the KGB was highly centralized and

was controlled rigidly from the top. The KGB central staff kept

a close watch over the operations of its branches, leaving the

latter minimal autonomous authority over policy or cadre selection.

Moreover, local government organs had little involvement in

local KGB activities. Indeed, the high degree of centralization

in the KGB was reflected in the fact that regional KGB branches

were not subordinated to the local soviets, but only to the

KGB hierarchy. Thus, they differed from local branches of most

union-republic ministerial agencies, such as the MVD, which

were subject to dual subordination.

|

Party

personnel policy toward the KGB was designed not only to ensure

that the overall security needs of the state were met by means

of an efficient and well-functioning political police organization

but also to prevent the police from becoming too powerful and

threatening the party leadership. Party

personnel policy toward the KGB was designed not only to ensure

that the overall security needs of the state were met by means

of an efficient and well-functioning political police organization

but also to prevent the police from becoming too powerful and

threatening the party leadership.

|

Achieving

these two goals required the careful recruitment and promotion

of KGB officials who had the appropriate education, experience,

and qualifications as determined by the party. Judging from

the limited biographical information on KGB employees, the Komsomol

and the party were the main sources of recruitment to the KGB.

Russians and Ukrainians predominated in the KGB; other nationalities

were only minimally represented. In the non-Russian republics,

KGB chairmen were often representatives of the indigenous nationality,

as were other KGB employees. In such areas, however, KGB headquarters

in Moscow appointed Russians to the post of first deputy chairman,

and they monitored activities and reported back to Moscow. Achieving

these two goals required the careful recruitment and promotion

of KGB officials who had the appropriate education, experience,

and qualifications as determined by the party. Judging from

the limited biographical information on KGB employees, the Komsomol

and the party were the main sources of recruitment to the KGB.

Russians and Ukrainians predominated in the KGB; other nationalities

were only minimally represented. In the non-Russian republics,

KGB chairmen were often representatives of the indigenous nationality,

as were other KGB employees. In such areas, however, KGB headquarters

in Moscow appointed Russians to the post of first deputy chairman,

and they monitored activities and reported back to Moscow.

The KGB had a variety of domestic security functions.

It was empowered by law to arrest and investigate individuals

for certain types of political and economic crimes. It was also

responsible for censorship, propaganda, and the protection of

state and military secrets.

|

|

Headquarters of the KGB, Lubyanka,

Moscow.

In carrying out its task of ensuring state security,

the KGB was empowered by law to uncover and investigate certain

political crimes set forth in the Russian Republic's Code of

Criminal Procedure and the criminal codes of other republics.

According to the Russian Republic's Code of Criminal Procedure,

which came into force in 1960 and has been revised several times

since then, the KGB had the authority, together with the Procuracy,

to investigate the political crimes of treason, espionage, terrorism,

sabotage, anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, divulgence of

state secrets, smuggling, illegal exit abroad, and illegal entry

into the Soviet Union. In addition, the KGB was empowered, along

with the Procuracy and the MVD, to investigate the following

economic crimes: stealing of state property by appropriation

or embezzlement or by abuse of official position and stealing

of state property or socialist property on an especially large

scale.

|

|

Moscow, guard on the Red Square. |

|

|

In

carrying out arrests and investigations for these crimes,

the KGB was subject to specific rules that were set forth

in the Code of Criminal Procedure. The Procuracy was charged

with ensuring that these rules were observed. In practice,

the Procuracy had little authority over the KGB, and the latter

was permitted to circumvent the regulations whenever politically

expedient. In 1988 closing some of these loopholes was discussed,

and legal experts called for a greater role for the Procuracy

in protecting Soviet citizens from abuse by the investigatory

organs. As of May 1989, however, few concrete changes had

been publicized. In

carrying out arrests and investigations for these crimes,

the KGB was subject to specific rules that were set forth

in the Code of Criminal Procedure. The Procuracy was charged

with ensuring that these rules were observed. In practice,

the Procuracy had little authority over the KGB, and the latter

was permitted to circumvent the regulations whenever politically

expedient. In 1988 closing some of these loopholes was discussed,

and legal experts called for a greater role for the Procuracy

in protecting Soviet citizens from abuse by the investigatory

organs. As of May 1989, however, few concrete changes had

been publicized.

The

intensity of KGB campaigns against political crime varied

considerably over the years. The Khrushchev period was marked

by relative tolerance toward dissent, whereas Brezhnev reinstituted

a harsh policy. The level of political arrests rose markedly

from 1965 to 1973. In 1972 Brezhnev began to pursue détente,

and the regime apparently tried to appease Western critics

by moderating KGB operations against dissent. There was a

sharp reversal after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in

December 1979, and arrests again became more numerous. In

1986, Gorbachev's second year in power, restraint was reintroduced,

and the KGB curtailed its arrests. The

intensity of KGB campaigns against political crime varied

considerably over the years. The Khrushchev period was marked

by relative tolerance toward dissent, whereas Brezhnev reinstituted

a harsh policy. The level of political arrests rose markedly

from 1965 to 1973. In 1972 Brezhnev began to pursue détente,

and the regime apparently tried to appease Western critics

by moderating KGB operations against dissent. There was a

sharp reversal after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in

December 1979, and arrests again became more numerous. In

1986, Gorbachev's second year in power, restraint was reintroduced,

and the KGB curtailed its arrests.

The forcible confinement of dissidents in psychiatric

hospitals, where debilitating drugs were administered, was

an alternative to straightforward arrests. This procedure

avoided the unfavorable publicity that often arose with criminal

trials of dissenters. Also, by labeling dissenters madmen,

authorities hoped to discredit their actions and deprive them

of support. The KGB often arranged for such commitments and

maintained an active presence in psychiatric hospitals, despite

the fact that these institutions were not under its formal

authority. The Gorbachev leadership, as part of its general

program of reform, introduced some reforms that were designed

to prevent the abuse of psychiatric commitment by Soviet authorities,

but the practical effects of these changes remained unclear

in 1989.

In addition to arrests, psychiatric commitment, and other

forms of coercion, the KGB also exercised a preventive function,

designed to prevent political crimes and suppress deviant political

attitudes. The KGB carried out this function in a variety of

ways. For example, when the KGB learned that a Soviet citizen

was having contact with foreigners or speaking in a negative

fashion about the Soviet regime, it made efforts to set him

or her straight by means of a "chat."

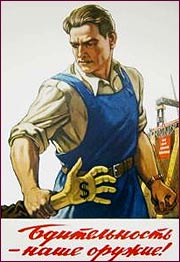

The KGB also devoted great efforts to political indoctrination

and propaganda. At local and regional levels, KGB officials

regularly visited factories, schools, collective farms, and

Komsomol organizations to deliver talks on political vigilance.

National and republic-level KGB officials wrote articles and

gave speeches on this theme. Their main message was that the

Soviet Union was threatened by the large-scale efforts of Western

intelligence agencies to penetrate the country by using cultural,

scientific, and tourist exchanges to send in spies. |

|

|