|

For

the KGB, 1967 was not the best of times. A few years earlier,

the Penkovsky case had blown up in the agency's face. Oleg

Penkovsky, a colonel in Soviet intelligence, had been passing

top-level intelligence information to the British, including

names and identities of several hundred Soviet agents. He

was a voluminous source of detailed information like the kind

that enabled President Kennedy to act so effectively against

Khrushchev at the time of the Cuban missile crisis. For

the KGB, 1967 was not the best of times. A few years earlier,

the Penkovsky case had blown up in the agency's face. Oleg

Penkovsky, a colonel in Soviet intelligence, had been passing

top-level intelligence information to the British, including

names and identities of several hundred Soviet agents. He

was a voluminous source of detailed information like the kind

that enabled President Kennedy to act so effectively against

Khrushchev at the time of the Cuban missile crisis.

Penkovsky was caught, tried, and executed, but not before

very serious damage had been done to the worldwide KGB operation.

The overwhelming Israeli defeat of Egypt, armed and advised

by the Soviet Union, in the 1967 "Six-Day War" also

reflected little credit on either the Soviet military or the

KGB. A serious shakeup in the KGB was badly needed.

As Andropov took charge

of the agency that year, he once again found others in powerful

positions who were able to help him conduct such a shakeup

and whose assistance considerably eased his path to greater

power. One of these was Sergei Vinogradov, a general in the

KGB. He had served as Soviet Ambassador to Turkey, Egypt and

France. As one of the most powerful men in Soviet foreign

policy, Vinogradov was able to bring Andropov into the highest

Kremlin councils.

In addition, there was Alexander Panyushkin, a senior

member of the Personnel Department of the Party Central Committee,

who was responsible for all higher-level appointments of Soviet

citizens working abroad in embassies, trade, and other activities.

Friendship with Panyushkin was especially useful for the ambitious

Andropov, because Panyushkin had been Soviet Ambassador to

both the United States and China. Both of these men were of

great influence on Andropov and greatly broadened his knowledge

of the diverse world outside the Soviet empire.

Andropov was also able to call on assistance from

the man who certainly must rank as the greatest spy of the

twentieth century, if not of all time - the Englishman, Harold

A.R. "Kim" Philby. By the end of World War II, Philby

was head of the Soviet Section of British intelligence and

later served as liaison between the British intelligence services

and the CIA in Washington. It appears that the initial recruiting

of Philby may have been made in 1933 by Vinogradov. The two

certainly met in Turkey in 1947, when Vinogradov was Soviet

Ambassador in Ankara. In 1963, after a brilliant career as

a Soviet agent working in the British intelligence service

spanning nearly three decades, Philby sought safety in Moscow.

In the eyes of the KGB, Philby was seen as almost

god-like. His authority on espionage matters was never questioned.

He had everything - culture, knowledge, intelligence, education,

experience, superb mannerism every way the antithesis of many

KGB officers of the time. Myths about Philby's exploits circulated

through-out the KGB, and imitation of this remarkable spy

became inevitable.

Many in the West may have felt that Philby was enjoying

well-deserved rest and retirement in Moscow, but the fact

is that he became both friend and adviser to Yuri Andropov.

Through their relationship, the KGB was transformed from an

effective but somewhat crude intelligence agency to a tough

and increasingly sophisticated global operation.

Reorganizing any Soviet bureaucracy, even the secret

police, for greater efficiency is a monumental task, but Andropov

and Philby were able to bring about the essential changes.

One of the greatest needs was to improve the quality of KGB

officers and agents. The top students from the Institute of

International Relations were recruited directly by the KGB.

Not only were these young men far better educated, they also

had to demonstrate a high level of intellectual capability

and a potential for a well-mannered and sophisticated personality.

Philby and Andropov knew that really effective KGB operatives

would have to be able to mix and be accepted in the highest

levels of diplomacy, business, and society throughout the

world.

Although membership in the KGB was not often the first

career choice of many of these brighter young men, they knew,

as does everyone in the Soviet Union, that KGB officers have

perks and privileges far above those in other more distinguished

and accepted professions. KGB officers receive much higher

pay-up to five times that of a qualified engineer, and several

times that of an important professor. Beyond that there are

the other benefits, usually more important than mere rubles:

buying privileges at special food and clothing stores, hospitals

and health services of a quality far above those available

to ordinary Soviet citizens, cars, as well as special admission

to sports, cultural and recreational events and facilities.

The KGB was able to make offers to the best and brightest

that few were able to refuse.

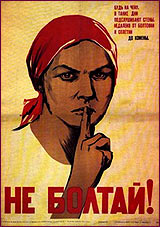

A new domestic propaganda campaign was launched to

improve the image of the KGB. Television and motion pictures

began showing a whole succession of Soviet secret police agencies

in the most favorable light. The exceptional exploits of spy

Maxim Isaev and Richard Sorge in

Japan became a popular television series, though it was never

shown that Sorge was finally caught and executed by the Japanese

in 1944. KGB officers and agents invariably appear as smooth,

suave and cosmopolitan, outsmarting the enemy all over the

world, and every time for the salvation and greater glory

of the Soviet Union. (These new Soviet media heroes are something

of a James Bond type, but without the fancy gadgetry of the

Bond films, and never bedding down with beautiful women at

the slightest opportunity.)

Although the KGB, in its international operation has

shown a high level of sophistication combined with the use

of the latest technological advances, its all-seeing and omnipotent

domestic investigation and control activities continue to

manifest the rough-and-tough characteristics of an earlier

KGB. There has, however, been a much greater use of the instruments

of contemporary psychology and psychiatry, as well as hal-lucinogenic

and other drugs. The simplistic rule of thumb continues:

if you oppose the Soviet system, you must be insane.

|