Dramatic

and confusing changes in what used to be the Soviet Union have

transformed the world in which we live. Dramatic

and confusing changes in what used to be the Soviet Union have

transformed the world in which we live.

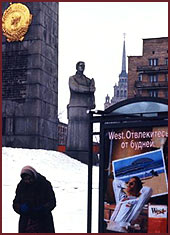

Russia's economic situation has deteriorated since the beginning

of Gorbachev's Perestroyka,

which announced moving from centrally planned economy to a market

economy.

The absence of a clear economical doctrine and means

led to destruction of internal economical structure and declining

of industries.

In

its turn, it led to significant raise of unemployment, with

unofficial estimates about 9-10%. Russian health and education

systems, which used to be of the highest standard during the

Soviet times, were slowly deteriorating. Inflation, started

in 1992, reached its peak in 1994, and increased 10 000% by

the end of 1997. In 1998 the government implemented a 1000%

denomination of national currency (Ruble), turned back prices

from thousands rubles to rubles. In

its turn, it led to significant raise of unemployment, with

unofficial estimates about 9-10%. Russian health and education

systems, which used to be of the highest standard during the

Soviet times, were slowly deteriorating. Inflation, started

in 1992, reached its peak in 1994, and increased 10 000% by

the end of 1997. In 1998 the government implemented a 1000%

denomination of national currency (Ruble), turned back prices

from thousands rubles to rubles.

The Soviet Union had a planned socialist economy,

in which the central government controlled everything from production

planning and prices to distribution. The Soviet satellite states

in Eastern Europe had planned economies as well. After the breakup

of the USSR, Russian reformers were confronted with the daunting

task of building a modern capitalist economy while simultaneously

striving to create a democratic state based on effective laws

and reliable administrative structures. The collapse of Communism

in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s and the dissolution of the

Soviet Union at the end of 1991 disrupted the close economic

relations Russia had previously enjoyed with neighboring Communist

states and other Soviet republics.

Political

turmoil and uncertainty inside the Russian government also contributed

to the country’s economic woes. Compared with most of the

former planned economies of Eastern Europe, Russia experienced

an unusually severe and protracted drop in officially reported

economic output. Political

turmoil and uncertainty inside the Russian government also contributed

to the country’s economic woes. Compared with most of the

former planned economies of Eastern Europe, Russia experienced

an unusually severe and protracted drop in officially reported

economic output.

Domestic policy in the Gorbachev

era was conducted primarily under three programs, whose names

became household words: perestroika (rebuilding), glasnost

(public voicing), and demokratizatsiya (democratization).

The first of these was applied primarily to the economy, but

it was meant to refer to society in general. Over the course

of Soviet rule, society in the Soviet Union had grown more urbanized,

better educated, and more complex. Old methods of exhortation

and coercion were inappropriate, yet Brezhnev's government had

denied change rather than mastered it. Despite Andropov's

efforts to reintroduce some measure of discipline, the communist

superpower remained stagnant. Once Gorbachev began to call for

bolder reforms, the "acceleration" gave way to perestroika.

From

modest beginnings at the Twenty-Seventh Party Congress in 1986,

perestroika, Mikhail Gorbachev's program of economic, political,

and social restructuring, became the unintended catalyst for

dismantling what had taken nearly three-quarters of a century

to erect: the Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist totalitarian state. From

modest beginnings at the Twenty-Seventh Party Congress in 1986,

perestroika, Mikhail Gorbachev's program of economic, political,

and social restructuring, became the unintended catalyst for

dismantling what had taken nearly three-quarters of a century

to erect: the Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist totalitarian state.

The world watched in disbelief but with growing admiration

as Soviet forces withdrew from Afghanistan, democratic governments

overturned Communist regimes in Eastern Europe, Germany was

reunited, the Warsaw Pact withered away, and the Cold War

came to an abrupt end.

In the Soviet Union itself, however, reactions to

the new policies were mixed. Reform policies rocked the foundation

of entrenched traditional power bases in the party, economy,

and society but did not replace them entirely. Newfound freedoms

of assembly, speech, and religion, the right to strike, and

multicandidate elections undermined not only the Soviet Union's

authoritarian structures, but also the familiar sense of order

and predictability. Long-suppressed, bitter inter-ethnic,

economic, and social grievances led to clashes, strikes, and

growing crime rates.

Gorbachev introduced policies designed to begin establishing

a market economy by encouraging limited private ownership

and profitability in Soviet industry and agriculture. But

the Communist control system and over-centralization of power

and privilege were maintained and new policies produced no

economic miracles. Instead, lines got longer for scarce goods

in the stores, civic unrest mounted, and bloody crackdowns

claimed lives, particularly in the restive nationalist populations

of the outlying Caucasus and Baltic states.

On August 19, 1991, conservative elements in Gorbachev's

own administration launched an abortive coup to prevent the

signing of a new union treaty the following day and to restore

the party's power and authority. Boris Yeltsin, who had become

Russia's first popularly elected president in June 1991, made

the seat of government of his Russian republic, known as the

White House, the rallying point for resistance to the organizers

of the coup. Under his leadership, Russia embarked on even more

far - reaching reforms as the Soviet Union broke up into its

constituent republics and formed the Commonwealth of Independent

States.

|

|

|

|

|

Radical

Reforms Radical

Reforms

On 11 March 1985, 54-year-old Mikhail Gorbachev was

elected the new general secretary of the Communist Party.

Following in the footsteps of such past rulers as Ivan

the Terrible, Peter the Great,

Stalin, and Brezhnev, Gorbachev

inherited a stagnating economy, an entrenched bureaucracy,

and a population that had lived in fear and mistrust of their

previous leaders. Gorbachev's first actions were to shut down

the production and sale of vodka and to ardently pursue Andropov's

anticorruption campaign; one of the first to go was Leningrad

party boss Grigory Romanov.

In 1986, when Gorbachev introduced the radical reform

policies of perestroika (restructuring), he emphasized that

past reforms hadn't worked because they didn't stress the

"involvement of the people in

modernizing and restructuring the country." Perestroika

implemented more profit motives, quality controls, private

ownership in agriculture, decentralization, and multicandidate

elections. Industry concentrated on measures promoting quality

over quantity; private businesses and cooperatives were encouraged;

farmers and individuals could now lease land and housing from

the government and keep the profits made from selling produce

grown on private plots: hundreds of ministries and bureaucratic

centers were disbanded. A law was passed that allowed individuals

to own small businesses and hire workers as long as there

was "no exploitation of man

by man." In the campaign for demokratizatsiya,

open elections were held. Glasnost let truths surface from

the Stalin and Brezhnev years.

As Peter the Great had understood,

modernization meant Westernization, and Gorbachev reopened

the window to the West. With the fostering of private

business, about five million people were employed by over

150,000 cooperatives. After 1 April 1989, all enterprises

were allowed to carry on trade relations with foreign partners.

This triggered the development of joint ventures. Multimillion

dollar deals were established with Western companies such

as Chevron, PepsiCo, Eastman-Kodak, McDonnell's, Time-Warner,

and Occidental Petroleum.

At the 1986 Iceland Summit, Gorbachev proposed to

sharply reduce the Soviet stockpile of ballistic missiles.

In December 1987, Gorbachev and US President Ronald Regain

signed a treaty at the Washington Summit to eliminate intermediate

nuclear missiles. "I do think

the winter of mistrust is over," declared

Premier Nikolai Ryzhkov.

During a visit to Finland in October 1989, Gorbachev

declared that "the Soviet Union

has no moral or political right to interfere in the affairs

of its East European neighbors. They have the right to decide

their own fate." By the end of 1989, every

country throughout Eastern Europe saw its people protesting

openly for mass reforms; not in this century had there been

such sweeping political change. The Iron Curtain crumbled,

symbolized most poignantly by the demolishing of the wall

between East and West Berlin.

In December 1989, Gorbachev met with US President George

Bush at the Malta Summit, where the two agreed that "the

arms race, mistrust, psychological and ideological struggle

should all be things of the past."

Article

about Perestroika, article

"Gorbachev and Perestroika".

|

|