|

The

history of Russia encompasses a vast range of revolutionary

activity, aimed at the overthrow of the autocracy, from the

unsuccessful uprising of Stepan Razin to the bloody upheaval

of 1917. For the most part, the early revolts were provoked

by the common folk who lacked functional knowledge of politics

and economics to implement concrete reforms had they succeeded. The

history of Russia encompasses a vast range of revolutionary

activity, aimed at the overthrow of the autocracy, from the

unsuccessful uprising of Stepan Razin to the bloody upheaval

of 1917. For the most part, the early revolts were provoked

by the common folk who lacked functional knowledge of politics

and economics to implement concrete reforms had they succeeded.

In the early19th century, however, the tide changed

direction as revolutionary ideas began to permeate the minds

of young noblemen who, having witnessed the benefits delivered

by the constitutional government to the countries of Western

Europe, were prompted to release their motherland from the

manacles of autocratic oppression.

Appropriately named after the unsuccessful uprising

of December 14, 1825 against Tzar Nicholas I, these men entered

the pages of history as the Decembrists.

Although

the Decembrist insurrection completely failed, it was nonetheless

the first attempt in modern Russian history to overthrow the

absolutist regime whose leaders pursued specific political

goals: reorganization of the government and abolition of serfdom. Although

the Decembrist insurrection completely failed, it was nonetheless

the first attempt in modern Russian history to overthrow the

absolutist regime whose leaders pursued specific political

goals: reorganization of the government and abolition of serfdom.

For the first time in the history of Russia, there

existed an influential group of society that held conception

of Russian state as distinct and separate from the ruler and

administrative institutions. Intoxicated with the progressive

ideas of Western Enlightenment, these young men undertook

an onerous task of eradicating the absolutist regime and backwardness

of their country.

Socially,

nineteenth century Russia developed along the lines very different

from those of Western Europe. General backwardness of the

Russian society, particularly evident in the dominance of

agriculture and enslavement of the peasantry, contrasts sharply

with the rise of modern urban capitalistic state in the countries

of Western Europe. The impact of the delayed progress was

not as poignantly perceived until the War

of 1812 and subsequent exposure to the Western culture

saturated with sentiments of individual rights and freedoms

and fashioned in the manner of a contemporary industrial state. Socially,

nineteenth century Russia developed along the lines very different

from those of Western Europe. General backwardness of the

Russian society, particularly evident in the dominance of

agriculture and enslavement of the peasantry, contrasts sharply

with the rise of modern urban capitalistic state in the countries

of Western Europe. The impact of the delayed progress was

not as poignantly perceived until the War

of 1812 and subsequent exposure to the Western culture

saturated with sentiments of individual rights and freedoms

and fashioned in the manner of a contemporary industrial state.

Politically, Russia was pushed to the backfront due

to its staunch adherence to autocratic government structure

long abolished in the modernized, constitutional European

countries. Under the traditionally domineering Russian monarchs,

the nobles were victimized by the arbitrary display of monarchical

power as much as the peasants since their socio-economic well-being

depends on the whimsical benevolence of the czar who controls

the economic status of the nobility through regulation of

their estates. As members of nobility began to claim their

independence from the czar, a schism developed between the

state and the aristocracy.

Failure of the monarchy to take nobility into its confidence

resulted in estrangement of the latter from state affairs

producing an irremediable cleavage between the czar and the

nobles. Comprised of the most intellectually advanced people

of the time, intelligentsia issued its the first challenge

to the absolutist authority in the form of the Decembrist

uprising.

Decembrists,

in Russian history, members of secret revolutionary societies

whose activities led to the uprising of Dec., 1825, against

Czar Nicholas I. Formed after the Napoleonic Wars, the groups

comprised officers who had served in Europe and had been influenced

by Western liberal ideals. They advocated the establishment

of representative democracy but disagreed on the form it should

take; some favored a constitutional monarchy, while others

supported a democratic republic. Their poorly organized rebellion

was precipitated by the confusion surrounding the succession

to the throne on the death of Alexander I. The more moderate

members persuaded several regiments in St. Petersburg to refuse

their oath of allegiance to the unpopular Nicholas l and to

demand that his elder brother, Constantine, who had secretly

renounced the throne in 1822, be made Tsar and grant a constitution. Decembrists,

in Russian history, members of secret revolutionary societies

whose activities led to the uprising of Dec., 1825, against

Czar Nicholas I. Formed after the Napoleonic Wars, the groups

comprised officers who had served in Europe and had been influenced

by Western liberal ideals. They advocated the establishment

of representative democracy but disagreed on the form it should

take; some favored a constitutional monarchy, while others

supported a democratic republic. Their poorly organized rebellion

was precipitated by the confusion surrounding the succession

to the throne on the death of Alexander I. The more moderate

members persuaded several regiments in St. Petersburg to refuse

their oath of allegiance to the unpopular Nicholas l and to

demand that his elder brother, Constantine, who had secretly

renounced the throne in 1822, be made Tsar and grant a constitution.

After some initial hesitation, Nickolas l firmly crushed

the revolt and was recognized as undisputed ruler of the Russian

Empire.

He firmly believed in the autocracy. Nickolas saw himself

as God's general in charge of Russia's well-being and every

citizen as his subordinate. He insisted his will be followed

at all times and ruled the Empire personally. Unlimited power,

such as held by Nickolas, would have been a disaster in the

hands of an immoral or unscrupulous man. The new Tsar was

neither. Nickolas was a convinced Orthodox Christian and truly

felt he was accountable to God for his actions. He felt his

own service to the nation was the prototype that all Russians

should follow. Nickolas' attitude was rigidly military. His

narrow-mindedness and egotism created the "Nickolas System",

based on "One Tsar, One Faith,

One Nation".

|

Tzar Nicholas l, in front of the

Winter Palace on the Senate Square, before shooting Desembrists,

V. Masutov, 1861.

The uprising, ill-conceived and badly led, was a disaster.

Over 3,000 of the soldiers were promptly arrested. Of these,

five were hanged. As if to sum up the officers’ frustration

with backward Russia, one remarked, upon only breaking his legs

on the scaffold, "They can’t

even hang a man properly in Russia." Over 120

of the conspirators were exiled.

The

partial source of the Decembrists' failure is to be located

precisely in their removal from the populace whose alleviation

they were campaigning. Although the Decembrists sincerely desired

allayment of the yoke of serfdom from the necks of the peasantry,

the idea of cooperation with the mob was repugnant even to the

most liberal Decembrists. As they confined themselves to the

intellectual circle, the Decembrists developed erroneous perceptions

of what freedom means to the Russian peasant. Although they

have lived side by side with the serfs from childhood, none

of the Decembrists truly understands the mind of the peasant. The

partial source of the Decembrists' failure is to be located

precisely in their removal from the populace whose alleviation

they were campaigning. Although the Decembrists sincerely desired

allayment of the yoke of serfdom from the necks of the peasantry,

the idea of cooperation with the mob was repugnant even to the

most liberal Decembrists. As they confined themselves to the

intellectual circle, the Decembrists developed erroneous perceptions

of what freedom means to the Russian peasant. Although they

have lived side by side with the serfs from childhood, none

of the Decembrists truly understands the mind of the peasant.

When in 1917 Lenin's Provisional Government became the

ruling clique of Russia, Lenin takes into notice the cardinal

miscue of Decembrists - failure to cooperate with the masses.

He writes,

"...we see three generations,

three classes at work in the Russian revolution. First come

the gentry and landowners, the Decembrists. The circle of these

revolutionaries is narrow. They are terribly far from the people."

The Decembrists’ insurrection made a profound impression

on Russia. It led both to the increasing police terrorism of

the tsarist government and to the spread of revolutionary activity

among the educated classes.

|

|

|

Sergey Zaryanko. Portrait of Princess

Trubetskaya, wife of the Desembrist Sergei Trubetskoy, 1856.

Oil on canvas. The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg.

|

|

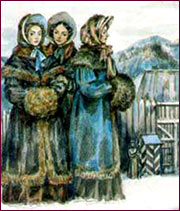

Decembrists' Wives

In a show of loyalty to their husbands, nearly all

the wives of Decembrists followed the men into exile.

Among them numbered eight prominent members of the

aristocracy. The most famous of these are Ekaterina Trubitskaya

and Maria Volkonskaya.

In order to strike the Decembrists totally out of their

lives, the Church and State passed a law whereby the Decembrist's

wives were considered widows and allowed to remarry within

their husbands' lifetime without an official divorce. However,

Yekaterina Trubetskaya turned down this offer, and so did

the other Decembrist's wives. When they departed for Siberia,

they left behind their privilegies as nobles and were reduced

to the status of exiled prisoners' wives, with restricted

rights of travel, correspondence and property ownership. They

were not allowed to take their children with them, and were

not always allowed to return to the European part of Russia

even after their husbands' death.

But

nothing could stop these courageous women. Yekaterina Trubetskaya,

wife of the General Sergey Trubetskoi, was the first to leave

for Siberia (in July 1826). But

nothing could stop these courageous women. Yekaterina Trubetskaya,

wife of the General Sergey Trubetskoi, was the first to leave

for Siberia (in July 1826).

The beautiful Maria Volkonskaya, daughter of the General

N. Raevski, and a wife of General-Major Sergey Volkonsky,

just had a baby when her husband was exiled. Without telling

her family, she asked Tzar's permission to follow her husband

to Siberia. Forced to renounce all her possessions and titles,

she even had to leave her infant son behind. She followed

her husband to the salt, silver and lead mines where the workers

toiled from six in the morning until 11 at night, in chains.

The portrait of her holding her baby son Nicholas was the

only thing that reminded her of him during the 30 years that

she spent in Siberia. (The baby died 2 years after her departure.)

Here, the wives were allowed to visit them twice a

week. Eventually, the prisoners’ conditions improved.

Pushkin,

a friend of many of the Decembrists, wrote a poem about them

in 1827. He too was inspired by their tales of unconditional

love. The female protagonist of "Eugene Onegin"

is based on one of the wives.

Pushkin wrote in "Eugene Onegin":

"Love tyrannises

all the ages; but youthful, virgin hearts derive a blessing

from its blasts and rages, like fields in spring when storms

arrive."

In

an old wooden mansion in Irkutsk, Maria Volkonskaya would

sit at her inlaid table, surrounded by her Empire furniture,

her library of over three thousand books, her gilt Italian

music box and her opera glasses for the opera she never again

attended. Here, she would gaze out of the window and observe

her husband, once a famous general, pottering eccentrically

about his vegetable garden while the children of the poor

which she had adopted scurried about the house. In

an old wooden mansion in Irkutsk, Maria Volkonskaya would

sit at her inlaid table, surrounded by her Empire furniture,

her library of over three thousand books, her gilt Italian

music box and her opera glasses for the opera she never again

attended. Here, she would gaze out of the window and observe

her husband, once a famous general, pottering eccentrically

about his vegetable garden while the children of the poor

which she had adopted scurried about the house.

Despite the charitable deeds, the bejewelled balls,

the touching amateur dramatics, a sadness permeates the walls

of the Volkonsky house. The wives of the Decembrists were

still exiles, unable even to write to their relations for

the first terrible years. They gave up everything. Staring

absentmindedly out of the window, you can imagine her dreaming

back to the glorious Saint Petersburg of her youth, to the

balls of the immense Winter Palace,

to another life which was denied her.

She

died in 1863, seven years after the pardon Tsar Alexander

II finally granted the Decembrists. The Volkonskys returned

to the capital. But they were old now, and many of their friends

had died. Life and the city had moved on, and they felt like

strangers. At the end of her life she confided that she had

been happy, and perhaps happier, in Irkutsk. Reading at her

desk, dreaming of the opera, the sound of children’s

games echoing around the house. She

died in 1863, seven years after the pardon Tsar Alexander

II finally granted the Decembrists. The Volkonskys returned

to the capital. But they were old now, and many of their friends

had died. Life and the city had moved on, and they felt like

strangers. At the end of her life she confided that she had

been happy, and perhaps happier, in Irkutsk. Reading at her

desk, dreaming of the opera, the sound of children’s

games echoing around the house.

In 1839, Trubetskoy was deported to the small village

of Oyok, thirty-eight kilornetres from Irkutsk, and Yekaterina

Trubetskaya and their three daughters and son, who had been

born in Siberia, went with him. Although their relatives sent

them large sums of money, the family still had financial problems.

The Siberian soil tilled by the Decembrists became

for some of them a place of eternal rest. In the graveyard

of the Znamensky Monastery, there are small, modest monuments

of Baikal marble on the graves of Decembrists N. Panov, P.

Mukhanov, and V. Beschasny. Yekaterina Trubetskaya and her

children are also buried here.

Click

here to read more about Decembrists.

Another good website - Decembrists

of Siberia.

Tours

to Decabrists places in Siberia. V. Obolensky's article

"Decembrists and Russian Freemasons".

|

|