The

Romanov family ruled Russia from 1613 to 1855 and during this

time, Russia became a major European power. The first rulers

of this dynasty struggled to end internal disorder, foreign

invasion and financial collapse. The

Romanov family ruled Russia from 1613 to 1855 and during this

time, Russia became a major European power. The first rulers

of this dynasty struggled to end internal disorder, foreign

invasion and financial collapse.

For the first few generations, the Romanovs were happy

to maintain the statusquo in Russia. They continued to centralize

power, but they did very little to bring Russia up to speed

with the rapid changes in economic and political life that were

taking place elsewhere in Europe. Peter the Great decided to

change all of that.

|

Peter

I "the Great", Romanov (1672 - 1725) was proclaimed

Tzar at the age of 10, but due to a power struggle had to

rule under the patronage of his sister Sofia. He seized control

from her when he was just 17. Peter

I "the Great", Romanov (1672 - 1725) was proclaimed

Tzar at the age of 10, but due to a power struggle had to

rule under the patronage of his sister Sofia. He seized control

from her when he was just 17.

Peter was his father's youngest son and the child of

his second wife, neither of which promised great things.

Tsar Alexis, his father, also had three children by his

first wife: Feodor, Sophia and Ivan, a semi-imbecile. When Alexis

died in 1676 Feodor became Tsar, but his poor constitution brought

an early death in 1682. The family of Peter's mother succeeded

in having him chosen over Ivan to be Tsar, and the ten year-old

boy was brought from his childhood home at the country estate

of Kolomenskoe to the Kremlin.

No sooner was he established, however, than the Ivan's family

struck back. Gaining the support of the Kremlin Guard, they

launched a coup d'etat, and Peter was forced to endure the horrible

sight of his supporters and family members being thrown from

the top of the grand Red Stair of the Faceted Palace onto the

raised pikes of the Guard. The outcome of the coup was a joint

Tsar-ship, with both Peter and Ivan placed under the regency

of Ivan's elder and not exactly impartial sister Sophia. Peter

had not enjoyed his stay in Moscow, a city he would dislike

for the rest of his life.

|

|

With

Sophia in control, Peter was sent back to Kolomenskoe.

It was soon noticed that he possessed a penchant for war games,

including especially military drill and siegecraft. He became

acquainted with a small community of European soldiers, from

whom he learned Western European tactics and strategy. Remarkably,

neither Sophia nor the Kremlin Guard found this suggestive.

In 1689, just as Peter was to come of age, Sophia attempted

another coup--this time, however, she was defeated and confined

to Novodevichiy Convent. Six

years later Ivan died, leaving Peter in sole possession of

the throne. With

Sophia in control, Peter was sent back to Kolomenskoe.

It was soon noticed that he possessed a penchant for war games,

including especially military drill and siegecraft. He became

acquainted with a small community of European soldiers, from

whom he learned Western European tactics and strategy. Remarkably,

neither Sophia nor the Kremlin Guard found this suggestive.

In 1689, just as Peter was to come of age, Sophia attempted

another coup--this time, however, she was defeated and confined

to Novodevichiy Convent. Six

years later Ivan died, leaving Peter in sole possession of

the throne.

Rather than taking up residence and rule in Moscow,

his response was to embark on a Grand Tour of Europe. He amassed

a considerable body of knowledge on western European industrial

techniques and state administration, and became determined

to modernize the Russian state and to westernize its society.

He spent about two years there, not only meeting monarchs

and conducting diplomacy but also travelling incognito and

even working as a ship's carpenter in Holland.

Peter believed in starting from the bottom and working

his way up. He learned ship building from the Europeans he

invited to Russia, and built a ship himself. In 1697, he accompanied

an embassy to European courts as a carpenter named Peter Mikhailov.

He also served as seaman, soldier, barber and, to the discomfort

of his courtiers, as dentist.. Those of his companions

who fell ill and needed a doctor were filled with terror that

the Tsar will hear of their illness and appear with his instruments

to offer his services.

In 1698, still on tour, Peter received news of yet

another rebellion by the Kremlin Guard, instigated by Sophia

despite her confinement to Novodevichiy.

He returned without any sense of humor, decisively defeating

the guard with his own European-drilled units, ordering a

mass execution of the surviving rebels, and then hanging the

bodies outside Sophia's convent window. She apparently went

mad. The following day Peter began his program to recreate

Russia in the image of Western Europe by personally clipping

off the beards of his nobles. He even taxed Russians wearing

beards!!!

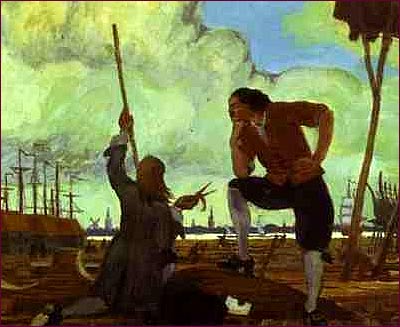

Mstislav Dobuzhinsky. Peter the

Great in Holland. Amsterdam, the Wharf of the East India Company.

Sketch. 1910. Oil on paper mounted on cardbord. The Tretyakov

Gallery, Moscow.

|

Peter's return to Russia and assumption

of personal rule hit the country like a hurricane.

He banned traditional Muscovite dress for all men, introduced

military conscription, established technical schools, replaced

the church patriarchy with a holy synod answerable to himself,

simplified the alphabet, tried to improve the manners of the

court, changed the calendar, changed his title from Tsar to

Emperor, and introduced a hundred other reforms, restrictions,

and novelties (all of which convinced the conservative clergy

that he was the antichrist).

In 1703 he embarked on the most dramatic of his reforms

- the decision to transfer the capital from Moscow to a new

city to be built from scratch on the Gulf of Finland. Over the

next nine years, at tremendous human and material cost, St.

Petersburg was created.

|

|

From the 1760s the Winter

Palace was the main residence of the Russian Tzars.

Peter also required all men to serve the state. Further

changes included abolishing hereditary positions with the creation

of the Table of Ranks that gave people privileges based on their

ability and position within the Table of Ranks. Along with changes

to the church, Peter increased the education that Russians received.

He created the first universities in Russia. Peter sent Russians

to be educated in the West, and imported skilled labour, military

and administrative experts from abroad. He encouraged smoking,

but taxed tobacco.

Perhaps the most important step that Peter took to ensure

the continuation of Western influence in Russia was to introduce

the practice of marrying royal princes to Western princesses.

Thereafter, nearly every tsar had a German wife, and

thus the German influence became strong in upper-class circles.

Peter himself had been married to the daughter of a Russian

nobleman in his youth in accordance with the earlier practice,

but he put her in a convent soon after he began to govern personally.

Perhaps realizing that under the circumstances he could not

hope to find a suitable Western princess for himself, he eventually

married his mistress Martha Scavronsky (later changed name to

Catherine).

|

A

servant girl, Martha Scavronsky, made a great career in the

Russian court. In her native Lithuania during the war she was

taken by the Russian soldier. Then she caught the eye of Prince

Boris Sheremetyev, who purchased her for one ruble and made

her one of his many mistresses. Prince Alexander

Menshikov, tsar's favorite 'borrowed' her for himself. Peter

I saw Martha in Menshikov's house and ordered, "When

I go to bed, you, beauty, take a candle and light the way."

According to the "etiquette" that meant

she was obliged to sleep with the tsar. In the morning Peter

paid her with a copper coin. Peter had granted himself this

modest sum for love expenses when still a young man and all

his life he strictly followed the tariff. Later, though, the

tsar married Martha and she became Catherine I, Empress of Russia.

She gave Peter three children and proved a fit companion for

the restless monarch. A

servant girl, Martha Scavronsky, made a great career in the

Russian court. In her native Lithuania during the war she was

taken by the Russian soldier. Then she caught the eye of Prince

Boris Sheremetyev, who purchased her for one ruble and made

her one of his many mistresses. Prince Alexander

Menshikov, tsar's favorite 'borrowed' her for himself. Peter

I saw Martha in Menshikov's house and ordered, "When

I go to bed, you, beauty, take a candle and light the way."

According to the "etiquette" that meant

she was obliged to sleep with the tsar. In the morning Peter

paid her with a copper coin. Peter had granted himself this

modest sum for love expenses when still a young man and all

his life he strictly followed the tariff. Later, though, the

tsar married Martha and she became Catherine I, Empress of Russia.

She gave Peter three children and proved a fit companion for

the restless monarch. |

|

|

Interesting Episode

The Frenchman Vilbois was Peter's favorite and aide-de-camp.

He was a drunkard, brawler and womanizer. Once Peter sent

this officer with an errand to his wife Catherine from St.

Petersburg to Kronstadt, where the tsarina lived in winter.

While traveling, Vilbois drank a bottle of vodka and came

to the place absolutely drunk. The ladies-in-waiting refused

to admit him to tsarina, saying that Her Majesty was sleeping.

“Wake her up immediately!” roared the officer. The

frightened ladies brought him to the tsarina’s bedroom

and left him before her bed for him to wake her up himself.

The drunk officer was so excited by the sleeping woman that

he completely forgot she was the tsarina. Catherine cried

for help, but unfortunately it came too late.

The

most interesting part in the story is the reaction of Peter. The

most interesting part in the story is the reaction of Peter.

The tsar grinned and said, ‘Vilbois, the brute, was drunk

and did not understand what he was doing. I bet, when he is

sober he'll not remember anything.” Peter sentenced the

Frenchman for exile for 2 years. However he returned him in

a couple of months with the following excuse: “benefits

from his knowledge and experience considerably exceed the

damage he had caused.”

Peter could excuse “accidents”, but never

deliberate unfaithfulness. When Peter found that William

Mons became Catherine's lover, he had the man beheaded.

Then he ordered the head of the unfortunate lover to be put

in a jar with alcohol. The jar stood in Catherine's bedroom

till Peter's death.

|

|

|

|

Peter

was free and easy in his relationship with people, but his social

manners were a mixture of the habits of a powerful aristocrat

and those of an artisan. Whenever he went visiting he would

sit down in the first vacant seat, if he was hot he would take

off his shirt in front of everybody. It was this habit of dispensing

with knives and forks at table that had so shocked the princesses

of Germany. He had no manners whatsoever and did hot consider

them necessary. Peter

was free and easy in his relationship with people, but his social

manners were a mixture of the habits of a powerful aristocrat

and those of an artisan. Whenever he went visiting he would

sit down in the first vacant seat, if he was hot he would take

off his shirt in front of everybody. It was this habit of dispensing

with knives and forks at table that had so shocked the princesses

of Germany. He had no manners whatsoever and did hot consider

them necessary.

Physically Peter was a giant of just under seven feet, and

at any gathering he towered a full head above everybody else.

Not only was Peter a natural athlete, but habitual use of ax

and hammer had developed his strength and 'manual dexterity

to such an extent that he was able to twist a silver platter

into a scroll.

Peter had other sides to his character. He spent time

and money generously in obtaining paintings and statues from

Italy and Germany which formed the foundations for the Hermitage

Collection at St. Petersburg.

The many pleasure palaces which he had built round his new capital

indicate his taste in architecture. At enormous cost he hired

the best European architects.

Peter

was never more than a guest in his own home. During his reign

he had traveled the length of Russia. He was also the first

Russian ruler to travel outside of Russia. As a result of

this perpetual mobility, Peter became so restless that he was

constitutionally incapable of staying in one place for any length

of time. He had such a long stride and used to walk so quickly

that his companions had to run to keep up with him. Peter

was never more than a guest in his own home. During his reign

he had traveled the length of Russia. He was also the first

Russian ruler to travel outside of Russia. As a result of

this perpetual mobility, Peter became so restless that he was

constitutionally incapable of staying in one place for any length

of time. He had such a long stride and used to walk so quickly

that his companions had to run to keep up with him.

If

Peter was not sleeping, traveling, feasting, or inspecting,

he was busy making something. When he was young and still inexperienced

he could never be shown over a factory or workshop without trying

his hand at whatever work was in progress. He found it impossible

to remain a mere spectator, particularly if he saw something

new going on. If

Peter was not sleeping, traveling, feasting, or inspecting,

he was busy making something. When he was young and still inexperienced

he could never be shown over a factory or workshop without trying

his hand at whatever work was in progress. He found it impossible

to remain a mere spectator, particularly if he saw something

new going on.

|

His

favorite occupation was shipbuilding, and no affairs of state

could detain him if there was an opportunity to work on the

wharves. He was such a competent marine architect that his contemporaries

said that he was the best shipwright in Russia, since he not

only could design a ship, but knew every detail of its construction.

Peter took a particular pride in this ability and he stinted

neither money nor effort in extending and improving Russia's

shipbuilding industry. His

favorite occupation was shipbuilding, and no affairs of state

could detain him if there was an opportunity to work on the

wharves. He was such a competent marine architect that his contemporaries

said that he was the best shipwright in Russia, since he not

only could design a ship, but knew every detail of its construction.

Peter took a particular pride in this ability and he stinted

neither money nor effort in extending and improving Russia's

shipbuilding industry.

After his death, it was found that nearly every place

in which he had lived for any length of time was full of the

model boats, chairs, crockery, and snuff-boxes he had made himself.

It is surprising that Peter ever found enough leisure to make

so many things. |

Peter generated considerable opposition during his reign,

not only from the conservative clergy but also from the nobility,

who were understandably rather attached to the status quo. His

reforms were not always popular. Some of them led to revolts

which Peter the Great had to suppress.

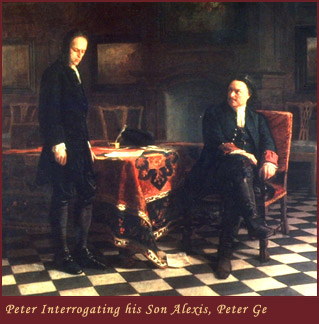

One of the most notable critics of his policies was his

own son Alexis, who naturally enough became the focus of oppositional

intrigue.

One of the most notable critics of his policies was his

own son Alexis, who naturally enough became the focus of oppositional

intrigue.

In fact, Alexis seemed to desire no such position, and in 1716

he fled to Vienna after renouncing his right to the succession.

Having never had much occasion to trust in others, Peter suspected

that Alexis had in fact fled in order to rally foreign backing.

After persuading him to return, Peter had his son arrested and

tried for treason. In 1718 he was sentenced to death, but died

before the execution from wounds sustained during torture.

|

Peter the Great decided that the ruler should nominate

his successor. The tsarship would no longer be a hereditary

position

However, Peter died without nominating an heir and at

his death the question of ascension to the throne was left unanswered.

There was no obvious choice either, as Peter had been married

twice and had 11 children, many of whom died in infancy and

the eldest son from his first marriage, Tzarevich Alexei died

from torture.

Peter himself died in 1725. Unlike previous monarchs,

he was not afraid of physical labour. In November 1724, he dived

into the cold northern ocean to assist in a ship rescue. It

led to his illness and death.

Peter the Great still remains one of the most controversial

figures in Russian history.

|

More than in any other period of Russian

history, the end of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth

centuries was an era of great events and changes for which a

single man was mostly responsible.

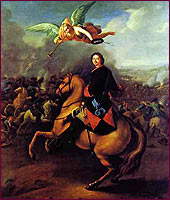

Peter the Great's reign transformed Russia. He strengthened

the rule of the tsar and westernized Russia while at the same

time making Russia a power in Europe and greatly expanding Russia's

borders. During his reign, Russia became an empire and Peter

became the first emperor of Russia.

|

It

is difficult to evaluate Peter's work. By his energy and ruthlessness

he modernized Russia to the extent that it was strong enough

to escape the fate of Poland and the Ottoman Empire, but the

deeper aspects of Western culture never penetrated below the

aristocracy, and the masses of the Russian people were forced

down lower than ever. They remained in ignorance, now separated

culturally as well as economically and socially from their superiors. It

is difficult to evaluate Peter's work. By his energy and ruthlessness

he modernized Russia to the extent that it was strong enough

to escape the fate of Poland and the Ottoman Empire, but the

deeper aspects of Western culture never penetrated below the

aristocracy, and the masses of the Russian people were forced

down lower than ever. They remained in ignorance, now separated

culturally as well as economically and socially from their superiors.

Although he was deeply committed to making Russia a powerful

new member of modern Europe, it is questionable whether his

reforms resulted in significant improvements to the lives of

his subjects.

After Peter's death Russia went through a great number

of rulers in a distressingly short time, none of whom had much

of an opportunity to leave a lasting impression. |

|