The

tragedy of Nicholas II, the Last Imperial Ruler of Russia, was

that he appeared in the wrong place in history. Equipped by

education to rule in the nineteenth century, where the world

seemed orderly, and equipped by temperament to be a constitutional

monarch, where a sovereign needed only be a good man in order

to be a good king. He lived and reigned in a transforming Russia

of the early twentieth century. The

tragedy of Nicholas II, the Last Imperial Ruler of Russia, was

that he appeared in the wrong place in history. Equipped by

education to rule in the nineteenth century, where the world

seemed orderly, and equipped by temperament to be a constitutional

monarch, where a sovereign needed only be a good man in order

to be a good king. He lived and reigned in a transforming Russia

of the early twentieth century.

The Emperor had the outstanding qualities of a man and

a ruler, but his favorite expression with regard to himself

in a close family circle was “I

am just a plain, common man.” He had an excellent

memory, exceptional energy and broad learning, a strong and

disciplined will power, an acute sense of morality, a great

awareness of his responsibilities. Devoted to his ideals, he

defended them with patience and persistence. Thoroughly honest,

he was a slave to his word and his loyalty towards the allies,

which was the reason of his death, proved it better than anything

else.

His instructions on the way to write an account of

the Russo-Japanese War were the following: “The

work must be based exclusively on bare facts … We have

nothing to hold back, as too much blood has already been shed.

Heroism deserves to be recorded along with defeats. We must

unfailingly strive to restore historical facts in their true

light.”

The Emperor was an implacable enemy of all the attempts

to idealize that which was unworthy; he himself spoke and

demanded nothing but the truth. Truth alone was what he looked

for everywhere.

|

Although

Nicholas was the Tsesarevich, he had no desire to be the Tsar

and would have rather been "a farmer in England".

But, alas, he was to become the Tsar. Nicholas and his family's

fate were sealed. Although

Nicholas was the Tsesarevich, he had no desire to be the Tsar

and would have rather been "a farmer in England".

But, alas, he was to become the Tsar. Nicholas and his family's

fate were sealed.

It was a great misfortune for the Tsar Nicholas II and the Tsarina

Alexandra that they ascended the throne so young.

Growing up, Nickolas's father, Emperor Alexander III, did

not let him participate in his father's meeting with counclers,

which was a large mistake, for if Nicholas had been more active

in his father's life as a Tsar, he would not made so many mistakes

during his rule.

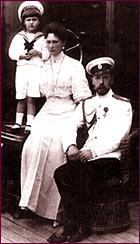

Nicholas II Alexandrovich Romanov (1868-1918) - last

Russian emperor, ruled from 1894 to 1917. Eldest son of Emperor

Alexander III (1845 - 1894) and Empress Maria Fedorovna (1847-1928).

He married (1894) a German Princess Alix Victoria Helene Luisa

Beatrice Hesse-Darmstadt (1872 - 1918) who, after converting

to Russian Orthodoxy, became Alexandra Fedorovna or Alix. |

Prior to her confirmation, Alexandra had to go through

a great moral struggle, when, loving the Tsarevich Nicholas,

and knowing that she was loved by him, she also knew that to

marry him she had to embrace the Orthodox faith.

Prior to her confirmation, Alexandra had to go through

a great moral struggle, when, loving the Tsarevich Nicholas,

and knowing that she was loved by him, she also knew that to

marry him she had to embrace the Orthodox faith.

German by birth, English by upbringing, Protestant by

her father’s faith, she became a true Russian with ever

fiber of her nature. She had a deep love for Russia and became

truly Orthodox in spirit, in thought, and in actions in the

services, very similar to those performed by religious peasant

women.

After the birth of her first child, the Empress gave

all her attention to her children; she personally fed them,

bathed them, selected their nurses and was constantly in the

nursery, not trusting them with anyone. She would spend hours

in the classroom, directing their studies. It often happened

that while discussing important questions regarding a new charitable

organization, she would be holding her baby in her arms, or

while signing some business documents she would be rocking a

baby’s cradle. In her free moments she was always engaged

in some work such as embroidering, knitting, or painting.

The Grand Duchesses, were also busy, always occupied

with some activity. Wonderful works and embroideries came

from their nimble little hands. The two oldest daughters,

Olga and Tatiana, worked together with their mother in their

military hospitals during the World War l. Working as common

Red Cross nurses, they changed the dressing of wounded men.

|

|

The Royal Wedding

One week prior the royal wedding of Nicholas and

Alexandra, Emperor Alexander III, Nicholas's father, died.

The Imperial Family all assembled at St.

Petersburg to meet the funeral train, and Princess Alix's

first entrance into her future capital was in a weary funeral

procession.

Princess Alix was dressed for her wedding in the Malachite

drawing-room of the Winter Palace.

Her hair was done in the traditional long side curls, in front

of the famous gold mirror of the Empress Anna Ioannovna, before

which every Russian Grand Duchess dresses on her wedding day.

The chief dressers of the ladies of the Imperial Family assisted,

and handed the crown jewels, which

lay on red velvet cushions. She wore numerous splendid diamond

ornaments and her dress was a heavy Russian Court dress of

real silver tissue, with an immensely long train edged with

ermine. The train was so heavy that, when it was not carried

by the chamberlains, she was almost pinned to the ground by

its weight.

The Emperor's marriage had been arranged so suddenly

that no preparations had been made for the young couple. No

festivities of any kind followed the marriage ceremony. It

took place in the morning, and immediately afterwards the

young Imperial couple drove to the Anichkov Palace, enthusiastically

cheered by the huge crowds which lined their route.

|

|

Letter

from Empress Alexandra to her sister. Letter

from Empress Alexandra to her sister.

Anichkov Palace,

December 10th, 1894.

"The ceremony in church reminded me so much of '84,

only both our fathers were missing - that was fearful-no kiss,

no blessing from either. But I cannot speak about that day

nor of all the sad ceremonies before. One's feelings you can

imagine. One day in deepest mourning, lamenting a beloved

one, the next in smartest clothes being married. There cannot

be a greater contrast, but it drew us more together, if possible...

If I only could find words to tell you of my happiness daily

it grows more and my love greater. Never can I thank God enough

for having given me such a treasure. He is too good, dear,

loving and kind, and his affection for his mother is touching,

and how he looks after her, so quietly and tenderly."

The Empress's character was very complex. Love for

her husband and children was its dominant trait. She was an

ideal wife and mother; her worst enemies could not deny her

this. She was not always logically reasonable when it was

a case of conflict between reason and affection. Her intellect

was always subordinate to her heart. In her dealings with

other people, her idealism often made her find in them the

good that her own nature led her to expect. Her inherent shyness,

which she was never able to conquer, was misunderstood and

considered pride.

The Emperor Nicholas and the Empress Alexandra were

everything to each other, and their devotion lasted all their

lives. Their natures were very different, but they had grown

into harmony with each other till they had reached that perfection

of understanding in which the tastes and habits of the one

are a development and continuation of those of the other.

The Empress had the stronger character, and in matters concerning

the Household or the children's education, which the Emperor

left in her hands, her wishes were law. If anyone referred

such questions to the Emperor, he always said "It is

as Her Majesty desires." He believed in her intuitive

good sense and depended on her judgment.

|

|

|

Letters from Tzar Nicholas II

to his wife Alexandra

Telegram, Novoborissov, 21 September, 1914.

"Sincere thanks for dear letter.

Hope you slept and feel well. Rainy, cold weather. In thought

and prayer I am with you and the children. How is the little

one? Tender kisses for all. Nicky."

Letter, Stavka, 5 April, 1915.

"MY BELOVED SUNNY,

I thank you from the depth of my old loving heart for your

two charming letters, the telegram and the flowers. I was

so touched by them. I was feeling so sad and downhearted,

leaving you not quite well, and remained in that state until

I fell asleep... Nicky."

Letter, Stavka, 31 March, 1916.

" MY BELOVED SUNNY,

At last I have snatched a minute to sit down and write to

you after a five days' silence - a letter is a substitute

for conversation, not like telegrams.

I thank you tenderly for your dear letters - your first

seems to have come so long ago! What joy it is to get several

in one day, (as I did) on the way, coming home!

During the journey I read from morning till night - first

of all I finished "The Man who was Dead," then

a French book, and to-day a charming tale about little Boy

Blue! I like it... I had to resort to my handkerchief several

times. I like to re-read some of the parts separately, although

I know them practically by heart. I find them so pretty

and true! ....

Now, my angel, my tender darling. I must finish. May God

bless you and the children! I kiss you and them fondly.

Eternally your old hubby NICKY."

Letter, Stavka. 23 February, 1917

" MY BELOVED SUNNY,

I read your letters with avidity before going off to sleep.

It was a great comfort to me in my loneliness, after spending

two months together. If I could not hear your sweet voice,

at least I could console myself with these lines of your

tender love... - The day was sunny and cold and I was met

by the usual public (people), with Alexeiev at the head.

He is really looking very well, and on his face there is

a calm expression, such as I have not seen for a long time.

We had a good talk together for about half an hour. After

that I put my room in order and got your telegram telling

me of Olga and Baby having measles. I could not believe

my eyes - this news was so unexpected. In any case, it is

very tiresome and disturbing for you, my darling. Perhaps

you will cease to receive so many people? You have a legitimate

excuse - fear of transmitting the infection to their families...

The stillness round here depresses me, of course, when I

am not working...I am sending you and Alexey Orders from

the King and Queen of the Belgians in memory of the war.

You had better thank her yourself. He will be so pleased

with a new little cross! May God keep you, my joy... NICKY.

|

|

|

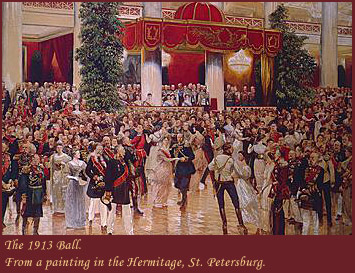

The Royal jubilee

The year 1913 was the jubilee of the Romanov dynasty,

when the completion of three hundred years of monarchy was

celebrated with great rejoicings.

Expressions of fealty reached the Imperial Family from

every part of the country. It seemed scarcely possible that

the people who hailed the Revolution

with enthusiasm four years later could have moved such addresses

of loyalty and taken part in such celebrations.

|

|

Emperor Nicholas II, last Emperor of

Russia. |

|

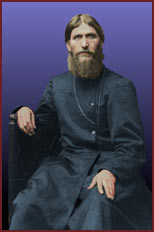

Rasputin and Tsarevitch Alexei

If the riddle of the blood disorder that helped bring

down Russia's Imperial Empire is to be solved, we must first

find the truth about a holy man's influence on the lives of

an Empress and her son. History has recorded that Grigory Rasputin,

possessed mysterious powers of healing that could stop the bleeding

episodes of Alexei, the only son and heir of Tsar Nicholas II.

|

In

the summer of 1904, the long-awaited heir to the throne was

born. He became the center of the family, the favorite. Alexei

was an exceptionally handsome boy, the most wonderful child

anyone could hope for. But alas, when he was two months old

the Empress discovered that he was afflicted with hemophilia,

a hereditary disease of the House of Hesse, now transmitted

tragically to him, the long awaited heir. In

the summer of 1904, the long-awaited heir to the throne was

born. He became the center of the family, the favorite. Alexei

was an exceptionally handsome boy, the most wonderful child

anyone could hope for. But alas, when he was two months old

the Empress discovered that he was afflicted with hemophilia,

a hereditary disease of the House of Hesse, now transmitted

tragically to him, the long awaited heir.

The Empress suffered agony, blaming herself to be responsible

for his condition. Alexandra's shame of this may have been one

of the factors why she turned to the uncouth holy man Gregory

Rasputin.

The entire story of Tsar Nicholas II and his Empress

Alexandra centres on the Spala episode of October 1912 when

their son Alexei appeared to be on the brink of death.

The Emperor wrote to his mother: “The

days from the 10th to the 23rd were the worst. The poor child

suffered greatly; the pain was sporadic, occurring every 15

minutes. He hardly slept at all, did not have the strength to

cry but only moaned, repeating the same words all over again:

“Lord have mercy on me.” I could not stand it but

had to remain in the room in order to relieve Alix who had exhausted

herself completely, spending every night at his bedside. She

bore this trial better than I, especially when Alexis’

sufferings were at their worst.”

|

One

can only imagine how the parents suffered. An eye witness of

Alexei’s illness write: “The

crown-prince lay in bed, and moaned pitiably, pressing his head

to his mother’s hand, his fine face bloodless, unrecognizable.

From time to time he stopped moaning to whisper only one word:

“Mama,” in which he expressed all his suffering, all

his heart-break. And the mother would kiss his hair, his forehead,

his eyes, as if by this caress she could lighten his pain, breathe

into him some of that life which was leaving him.” One

can only imagine how the parents suffered. An eye witness of

Alexei’s illness write: “The

crown-prince lay in bed, and moaned pitiably, pressing his head

to his mother’s hand, his fine face bloodless, unrecognizable.

From time to time he stopped moaning to whisper only one word:

“Mama,” in which he expressed all his suffering, all

his heart-break. And the mother would kiss his hair, his forehead,

his eyes, as if by this caress she could lighten his pain, breathe

into him some of that life which was leaving him.”

For a week and a half the boy displayed symptoms of pallor,

internal haemorrhaging, abdominal swelling, pain and bleeding

in the joints, delirium, and dangerously high fever, but he

suddenly began to recover after the arrival of a telegram sent

by Rasputin to the Empress Alexandra.

|

All

sorts of theories, from a reduction of stress and blood pressure

to claims of hypnosis, have been used in attempts to explain

how the words of a simple telegram could cure an eight year

old boy believed to have been dying from haemophilia. All

sorts of theories, from a reduction of stress and blood pressure

to claims of hypnosis, have been used in attempts to explain

how the words of a simple telegram could cure an eight year

old boy believed to have been dying from haemophilia.

Surrounded by doctors and advisors all predicting the

worst, only Rasputin gave her hope and reason to believe things

could get better. He did not heal Alexei's disease as historians

have suggested, but Rasputin did heal Alexandra's faith and

her belief that there could be a brighter future for her son.

Some say that it is incredible that the Empress of Russia

could pin her faith to such a person.

The appearance of such a personage in the precincts of

the Palace was bound to make a stir. The Emperor and Empress

had by this time realised that anyone to whom they showed any

special mark of favour would be immediately pecked at and intrigued

against. They imagined that this was the cause of the feeling

against Rasputin. When rumours against him were reported to

the Empress, she supposed them to be due to jealousy and class

prejudice.

|

There

was something in the Emperor, simple as he was, that made any

familiarity in his presence unthinkable; but Rasputin kept his

gruff way of speech and spoke as authoritatively to the Emperor

as he would have spoken to a commoner. There

was something in the Emperor, simple as he was, that made any

familiarity in his presence unthinkable; but Rasputin kept his

gruff way of speech and spoke as authoritatively to the Emperor

as he would have spoken to a commoner.

The Empress saw Rasputin solely with religious eyes,

neither the uncouth peasant, nor the man, but the helping spirit

sent in her hour of need. She trusted, from the first, that

his prayers might cure her son. She, who disliked all publicity,

hid the fact of the child's illness.

In the case of Alexandra Fedorovna, mysticism was combined

with a blind clinging to anything that might save her child,

easily understood by some Russian minds, in whom religion is

curiously mixed with superstition.

|

Hatred

for Rasputin, the man who was supposed to be responsible for

all the Government's mistakes became a real obsession. The feeling

against him became so intense that in 1916 a plot was formed

to murder him in order to save Russia. Hatred

for Rasputin, the man who was supposed to be responsible for

all the Government's mistakes became a real obsession. The feeling

against him became so intense that in 1916 a plot was formed

to murder him in order to save Russia.

Conspirators lured him to the Yusupov

Palace on the pretext that Prince Felix Yusupov would introduce

Rasputin to his beautiful wife.

Rasputin was first offered poisoned wine, the amateur

murderers not knowing that for the poison they chose alcohol

is an antidote. Their victim survived what appeared to be a

deadly dose. Prince Yussupov and Purishkevich then took Rasputin

into an adjoining room and, as he was admiring an ancient crucifix,

shot him several times in the back. Rasputin's strong frame

resisted even this, and when Prince Yussupov -returned to remove

his body, he got up and staggered across the room. More shots

were fired, this time with effect. The body was taken in a car

and thrown into a hole made in the frozen Neva. The strength

of the current drove the body down under the ice, and it was

washed ashore some days later. Rasputin does not seem to have

been dead even when he was thrown into the water, for the cords

bound round his body were loosened, and his rigid hand was folded

as if making the sign of the cross. |

Nicholas

II Romanov ruled Russia from 1895 to 1917 and lost power during

Russia's February Revolution, when in the spring of 1917 he

had to abdicate. The power was transferred to the Provisional

Government, but shortly after that Nicholas Romanov and his

family were arrested and were kept under close surveillance

at the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoye Selo, near the Russian

capital Petrograd (now St. Petersburg).

Romanovs were then transported to inner Russia to prevent them

from running away abroad or from being captured by the approaching

German troops. Russia's last tzar and his family spent the last

months in Yekaterinburg. During their time in housearrest, the

family came yet closer and really didn't want leave Russia.

They saw it as their duty to stay, and as the empress said:

"If it is god's will, we must

endure it to the very end…" And so they

did… Nicholas

II Romanov ruled Russia from 1895 to 1917 and lost power during

Russia's February Revolution, when in the spring of 1917 he

had to abdicate. The power was transferred to the Provisional

Government, but shortly after that Nicholas Romanov and his

family were arrested and were kept under close surveillance

at the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoye Selo, near the Russian

capital Petrograd (now St. Petersburg).

Romanovs were then transported to inner Russia to prevent them

from running away abroad or from being captured by the approaching

German troops. Russia's last tzar and his family spent the last

months in Yekaterinburg. During their time in housearrest, the

family came yet closer and really didn't want leave Russia.

They saw it as their duty to stay, and as the empress said:

"If it is god's will, we must

endure it to the very end…" And so they

did…

|

Nicholas with the kids. Picture was

taken by Alix.

Before leaving to Alexander

Palace in Tsarskoe Selo for house arrest, Emperor Nicholas

II insisted on taking leave of his troops by addressing to them

the following Order of the Day.

|

|

Last

Order of the Emperor Nicholas II.

8 (21) March, 1917. No. 371.

|

|

On

July 17, 1918 last imperial family of Russia was "executed"

on the orders of the local authorities and, allegedly, of

the Bolshevik leader Vladimir

Lenin. The bodies of Romanovs were then thrown into one

of abandoned mines. On

July 17, 1918 last imperial family of Russia was "executed"

on the orders of the local authorities and, allegedly, of

the Bolshevik leader Vladimir

Lenin. The bodies of Romanovs were then thrown into one

of abandoned mines.

As a tsar, and even after he abdicated, Nicholas II was

the head of the Russian Orthodox Church. After the assassination,

he and his family were revered by many as martyrs and numerous

miracles were attributed to them. The family was canonized as

royal martyrs by the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad in 1981.

|

|