Russian

Court Dress Russian

Court Dress

The Russian Imperial Court was a place of splendor and

pride. Court dress in Russia was a very specific thing. It was

introduced by Nicholas I in 1834 and loosely based on traditional

Russian styles.

The Russian Court was no different to other Courts in

that everyone vied to be the most fashionable and the most talked-about.

As the imperial capital, St Petersburg's

inhabitants from the highest to the lowest have always known

the importance of dressing to impress.

|

This

portrait shows the Empress Alexandra, wife of Tzar Nicholas

I, in a Russian court dress. This

portrait shows the Empress Alexandra, wife of Tzar Nicholas

I, in a Russian court dress.

Both Alexandra's beauty and her love of elegant things

are obvious in this portrait.

She's wearing many pieces of jewelry and an elaborate dress

which at the time was the standard court dress. The fanciful

headdress was based on a traditional Russian

costume. In her hand she's holding a little bouquet of fresh

cornflowers, the same color as her eyes.

|

"The

richness and splendour of the Russian court is above all pretentious

descriptions. The traces of ancient Asian magnificence are mixed

with European exquisiteness. A huge suite of courtiers either

follow or preceed the Empress. "The

richness and splendour of the Russian court is above all pretentious

descriptions. The traces of ancient Asian magnificence are mixed

with European exquisiteness. A huge suite of courtiers either

follow or preceed the Empress.

Luxurious and brilliant full dresses and abundancy

of precious stones on them are much more magnificent than at

any other European court... Of the luxury articles of the Russian

nobility we foreigners are most of all astonished with the abundancy

of precious stones shining on different parts of their costume...

Many of the noblemen are almost studded with diamonds",

wrote the English traveller and historian William Cox who visited

the Winter Palace receptions.

|

As

compared with magnificence of the court way of life the personal

requirements of Tsarina Catherine ll were moderate as she intentionally

pointed it out. The state secretary of Catherine II who described

the last ten years of her reign Gribovskoy indicated that she

wore a plain loose dress of grey or violet silk. Orders and

jewellery decorated her costume made of brocade or velvet all

in the same style only at gala receptions. As

compared with magnificence of the court way of life the personal

requirements of Tsarina Catherine ll were moderate as she intentionally

pointed it out. The state secretary of Catherine II who described

the last ten years of her reign Gribovskoy indicated that she

wore a plain loose dress of grey or violet silk. Orders and

jewellery decorated her costume made of brocade or velvet all

in the same style only at gala receptions.

She introduced a fashion of wearing "Russian style"

dresses at the court and used elements of national costume in

her attire.

|

"The

Russian court dress was exceedingly picturesque and was donned

for all bigger occasions. It consisted of amply cut velvet robes

over a tablier of white satin; the shape, with its train, and

wide, long-hanging sleeves, had something medival about it.

These robes were heavily embroidered in silver or gold and were

of every colour of the rainbow; the richest of all were of cloth

of gold or silver. A halo-shaped

cocoshnic with a veil hanging from beneath it inevitably accompanied

this costume, so that every woman appeared to have been crowned.

This unity of attire made all Russian court gatherings uniquely

picturesque, saturating them with colour and brilliance unlike

anything else; veritable pictures out of the "Thousand

and One Nights," Byzantine in splendour, with all the mysterious

gorgeousness of the East. In those days the processional entry

of the Russian Imperial family into festive hall or saint-haunted

church was a picture once seen never to be forgotten."

- Marie, Queen of Roumania, from the book "The Story of

My Life". "The

Russian court dress was exceedingly picturesque and was donned

for all bigger occasions. It consisted of amply cut velvet robes

over a tablier of white satin; the shape, with its train, and

wide, long-hanging sleeves, had something medival about it.

These robes were heavily embroidered in silver or gold and were

of every colour of the rainbow; the richest of all were of cloth

of gold or silver. A halo-shaped

cocoshnic with a veil hanging from beneath it inevitably accompanied

this costume, so that every woman appeared to have been crowned.

This unity of attire made all Russian court gatherings uniquely

picturesque, saturating them with colour and brilliance unlike

anything else; veritable pictures out of the "Thousand

and One Nights," Byzantine in splendour, with all the mysterious

gorgeousness of the East. In those days the processional entry

of the Russian Imperial family into festive hall or saint-haunted

church was a picture once seen never to be forgotten."

- Marie, Queen of Roumania, from the book "The Story of

My Life".

|

Although

she had already attended three balls that week, it would not

be unusual for a Russian woman of noble standing to look forward

to yet another night of festivity in the city. It would not

be unusual, as well, for her husband to complaine that each

flounce of her dress costs more than an abbot's robe of gold

brocade. Although

she had already attended three balls that week, it would not

be unusual for a Russian woman of noble standing to look forward

to yet another night of festivity in the city. It would not

be unusual, as well, for her husband to complaine that each

flounce of her dress costs more than an abbot's robe of gold

brocade.

Rich jewellery was worn at

all times and vertually all of it - rings, bracelets, necklaces,

tiaras, pins, shoe buckles, hair ornaments, watches, swords

- was studded with diamonds and other precious stones. The cold

Russian climate demanded equally sumptuous coats and hats, and

of course, these had to be examples of high fashion.

|

The

Russian costumes of the former times are scarcely ever worn

today though they serve a source of inspiration to many a fashion

designers throughout the world. The

Russian costumes of the former times are scarcely ever worn

today though they serve a source of inspiration to many a fashion

designers throughout the world.

The industrial development of the 20th century had put

its impact on the fashion designs introducing new technologies

and materials. Yet the motifs of the older days, the best traditions

of style and form are often used by modem designers to diverse

and make their top fashion creations especially picturesque

and luxurious.

The

Pavlovsk Museum has a large collection of costumes belonged

to different representatives of the Russian Imperial Family.

|

|

|

Portrait of the Empress Catherine

ll, Levitski.

|

|

|

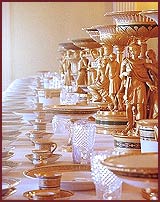

Table Settings

The

gold and silverware decorated with precious stones and pearls,

such as cups, loving-cups, win-cups and Korchiks (small dippers),

conjure up vivid pictures of court life during the 17th century. The

gold and silverware decorated with precious stones and pearls,

such as cups, loving-cups, win-cups and Korchiks (small dippers),

conjure up vivid pictures of court life during the 17th century.

Seramics, of all decorative art forms, was

the one most intensively cultivated in Imperial Russia.

Its development began not with Peter

the Great, who had sent his emissaries to Peking to wrest

from the Chinese their secrets of their exquisite ware, but

with his expansive, willful daughter, Empress Elizabeth.

|

Porcelain

was first brought to Europe by Marco Polo from China, and the

secret of its manufacturing remained unknown to Russians until

1740 when a young metallurgist was sent to Germany to study.

With this new knowledge, the first Russian porcelain factory

was opened in 1744 under the patronage of Empress Elizabeth,

and still exists today. Porcelain

was first brought to Europe by Marco Polo from China, and the

secret of its manufacturing remained unknown to Russians until

1740 when a young metallurgist was sent to Germany to study.

With this new knowledge, the first Russian porcelain factory

was opened in 1744 under the patronage of Empress Elizabeth,

and still exists today.

|

Though

beautiful dishes imported from Europe graced her table, she

nonetheless felt her surroundings were incomplete without an

abundant supply of porcelain produced in her own factories.

Elizabeth's pursuite was not self-serving for she saw it as

a means for generating commercial profit and as a way of nurturing

"home art".

The

primary business of the emerging porcelain industry was to supply

the royal courts with hard-paste porcelain table services, decorative

pieces for elaborate state banquets, and pieces for their private

use. Russian banquets often lasted up to nine hours and required

vast amounts of tableware. Porcelain's translucent beauty and

durability was valued as a decorative accent for the banquets.

The difficulty and expense of manufacturing porcelain demonstrated

the Russian empire's sophistication, and porcelain was often

presented as gifts to state and foreign visitors. The

primary business of the emerging porcelain industry was to supply

the royal courts with hard-paste porcelain table services, decorative

pieces for elaborate state banquets, and pieces for their private

use. Russian banquets often lasted up to nine hours and required

vast amounts of tableware. Porcelain's translucent beauty and

durability was valued as a decorative accent for the banquets.

The difficulty and expense of manufacturing porcelain demonstrated

the Russian empire's sophistication, and porcelain was often

presented as gifts to state and foreign visitors.

|

Traditional

Russian tea was poured into porcelaine cups from steaming samovars. Traditional

Russian tea was poured into porcelaine cups from steaming samovars.

Other examples of uniquely Russian objects found on banquet

tables were "kovshi". There were large ones from which

punch was poured and miniature ones that were used as saltcellars.

In time this unusual-looking object became so identifyed

with Imperial honor that it grew to be more desirable than any

other ceremonial gift.

|

|

Click

here to learn about the collection of Western European and

english porcelain in Pavlovsk Museum, one of the richest in

the suburban Imperial palaces.

|

|

|

|